February

Christian

Ruiz Berman

Christian Ruiz Berman’s paintings are a multilayered exploration of migration, adaptation, and ecology. The artist—who primarily works with oil and acrylic—uses visual media to ponder complex concepts, employing his paintbrush to, “examine the notion that each person, animal, and object is not only an essential component of the present moment, but an entangled element in a greater apparatus of constant change and adaptation,” as Ruiz Berman phrased it.

For example, one piece that the painter produced during his time at Fountainhead, Saint Valentine’s Return (2023), unpacks themes of “artificial intelligence, cultural objects, and intrapersonal connection.” The aforementioned work consists of two 20- by 30-inch paintings, creating a diptych that shows a striking arrangement of chrome-colored hands, crescent moons, and multicolored lines. The dynamic composition imbues the canvases with an ethereal quality, and the decision to make the painting diptych instead of a continuous piece lends to the disjointed and dream-like feel of it. Such formal choices (and others, like the addition of hands) also subtly hint at these ideas of human connection and subconscious realizations.

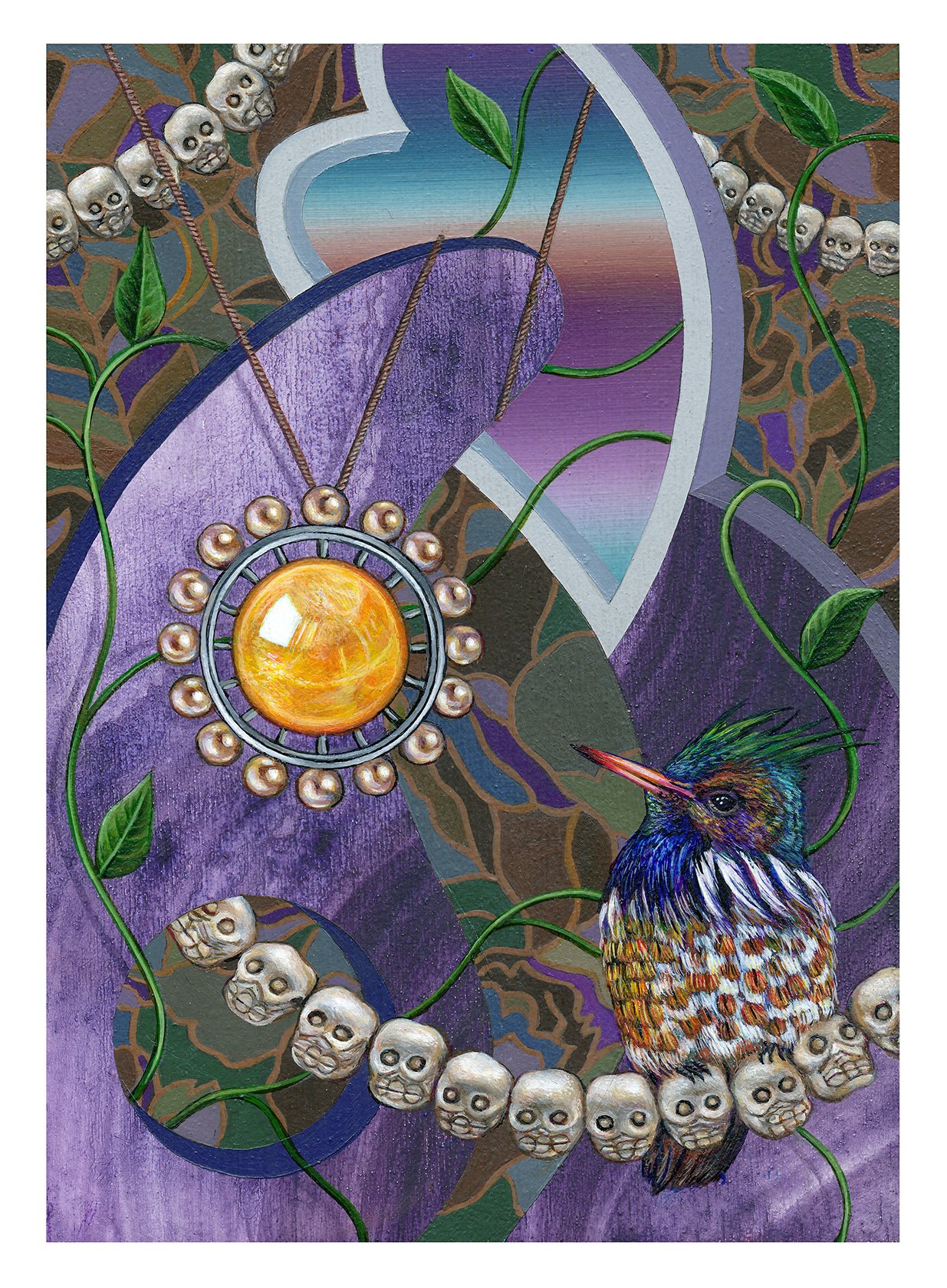

Other paintings in the artist’s oeuvre—such as Yepyollotli (the gift of every moment) (2022)—use historical artifacts to examine how we can find beauty in even the most quotidian occurrences. This piece depicts a wooden sculpture holding a chalice in its left hand, a bird with a string of pearls draped over its body, and a series of vines snaking around the other elements of the painting.

“Yepyollotli” is a word for “pearl” in Nahuatl, and the painting is an allegory for living with gratefulness, moment to moment,” Ruiz Berman explained. “The statue in the painting is a giver- he presents us with the pearls of each minute of life.”

This sensibility is omnipresent throughout Ruiz Berman’s practice, and the painter continues to find ways to bridge the gap between his personal heritage, collective experiences, and natural phenomena.

“My work emphasizes the idea that magic and surprise always happen as a result of shared experience, cross-cultural inspiration, and the subversion of established tropes and identities,” Ruiz Berman said. “I like to question the human animal’s centrality in the cosmos, and engage a fascination with the diversity and inherent tension of life’s web.”

–Isis Davis-Marks

Christian Ruiz Berman’s residency was generously sponsored in part by Hesty Leibtag and Terry Verk.

Charmed, I’m sure (2023); Acrylic on panel.

Clockwise from left: Spooky action at a distance (2023); acrylic on panel. Adar Rhiannon (time keepers) (2021); acrylic on panel. Cempatzuchitl (2021); acrylic on panel. A portrait of Berman in the studio by Jayme Gershen. Berman’s process involves precise detailing, as seen here on a work in progress at Fountainhead Residency; photographed by Jayme Gershen.

Miles

Greenberg

Miles Greenberg posits questions about human physiology in his practice: His body of work is comprised of engaging installations and performances to raise quandaries about how people relate to their surroundings.

“The moment becomes part of the provenance,” Greenberg said. “Every person who’s in the space at a given moment will get recorded and documented in the space in the way that it looks at that time. I’ve done things in spaces that have changed and evolved over time.”

His recent performance at Pace Gallery, Fountain II (2023), exemplifies this approach. The piece consisted of two people standing atop a white pedestal that sat inside a pool of blood-red liquid. Fountain II was, indeed, a meditation on human emotion and how devastating despair can feel; it served as a sequel to one of Greenberg’s earlier works—Fountain I (2022)—which was a reflection on the “final stages of heartbreak—when one finally turns one’s entire body inside out to reach a sort of ecstasy,” according to Pace’s website. In another one of the artist’s works, Oysterknife (2020), the artist briefly lost consciousness after walking on a treadmill for 24 hours, showing what can happen when one tests the confines of one’s corporeal form.

“I’m [...] interested in what lies beyond the limitations of the body,” Greenberg said. “But without going way hardcore—it still has to be authentic in some capacity.”

Greenberg gives life to these ideas through his meticulous preparation process and his research practice, much of which is centered around anatomy and biology.

“It depends on the piece, but typically the timeline is: Five plus months [prior to the performance] is when I’ll start doing research,” Greenberg said. “And then two months out, we start pre-production, and then a month out [we’ll be] properly producing and then like, four to six weeks is how long I usually train my body.”

At Fountainhead, Greenberg was able to prepare for new performances in a free and open-ended way, which allowed for him to research, create artifacts, and experiment with his studio practice.

“I think the [Fountainhead] team really understood the kind of asset that [performance art] could be for an institutional setting,” Greenberg said. “They took the time to understand the sort of dynamic of my work and what I’ve tried to leave behind and when I’m able to produce [it].”

–Isis Davis-Marks

Miles Greenberg’s residency was generously sponsored in part by Hesty Leibtag and Terry Verk.

Greenberg in Landscape with Figures (2022), a durational performance that lasts between seven and twelve consecutive hours.

Clockwise from left: Still from Etude pour Sebastien (2023); a five hour durational performance commissioned by the Musee de Louvre in Paris, France. Late October (2021); sculptures of steel, high-density urethane, enamel installed in volcanic rock, water, kaolin, and pigment. Greenberg sketches his ideas for conceptual performances at Fountainhead Residency, photographed by Jayme Gershen. Greenberg’s process often involves floor mapping to organize the specifics of each performative work. Still from Pneumotherapy II (2020); a durational performance series that focuses on a different part of the body in each iteration, performed at Perrotin in New York. A portrait of Greenberg in his studio at Fountainhead Residency, photographed by Jayme Gershen.

Tamara Santibañez

Tamara Santibañez uses a variety of media—from sculpture to video to painting—to raise questions about how we form conceptions of ourselves, how language can codify power dynamics, and how objects can help people draw associations.

“It’s nice to feel like I can revisit the same idea in multiple mediums and see how an image functions differently,” Santibañez said. “I like to be intentional in the different components of a piece. For example, if I’m making a keychain sculpture, I can do all the leather pieces myself rather than having to source them somewhere and can just be really specific about what they look like.”

This sense of intentionality is omnipresent in Santibañez’s oeuvre. In addition to their visual arts practice, the multimedia creator also studies oral history, and recently received a degree in it from Columbia University. Santibañez’s dedication to scholarship is clear in their practice, and their pieces tell nuanced stories about complicated subjects by including voices from a plurality of perspectives. One example of this is their book Tattooing as Liberation Work (2021), which discusses the power dynamics and history of tattooing.

“I’ve been thinking about access,” Santibañez said. “I’ve also been thinking about complicity in an era of representation or an era where certain marginalized identities are considered to be an asset in new ways.”

In addition to their experience in oral history and writing, Santibañez remains committed to making objects. The artist uses their visual practice to raise questions about how we ascribe meaning to accessories and patterns, and certain motifs such as calla lilies appear frequently in their work.

“I like to maintain that sense of openness and ambiguity,” Santibañez said. “I never want to feel like I’m dictating to the viewer what they shouldn’t be experiencing. And so I try to embed layers of references and images; I try to leave enough room for the person to have their own conclusions, and hopefully to generate some of their own questions or problems.”

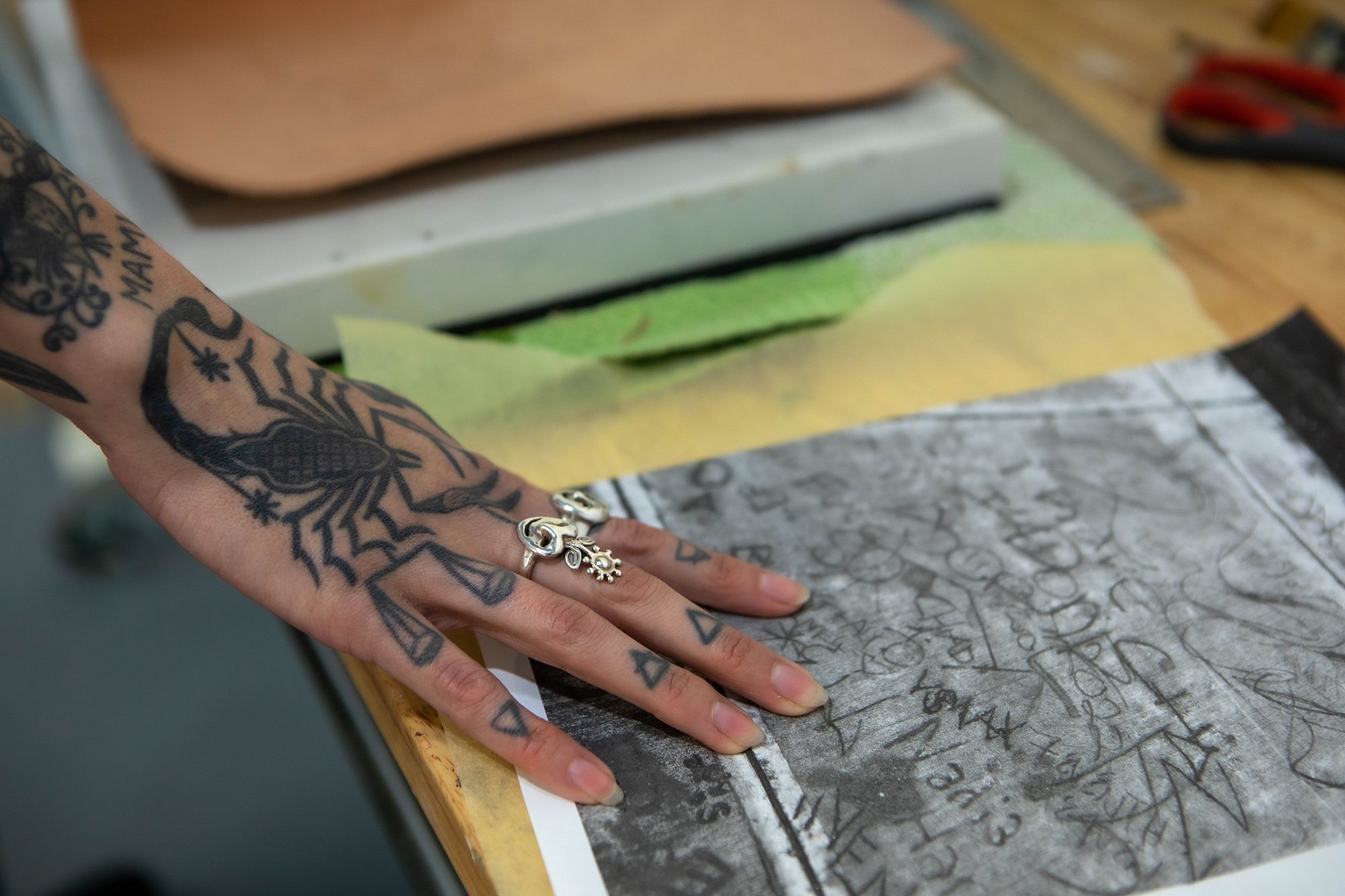

During their experience at the residency, Santibañez took the time to work through different aspects of their practice that they hadn’t experimented with in years.

“When I was at Fountainhead, I was pretty much doing all leather, working and drawing on leather,” Santibañez said. “Which is a practice I’ve had for a while, but I hadn’t really worked in it in a few years, partially from not having a studio space because it’s a lot of hammering.”

–Isis Davis-Marks

Tamara Santibañez’s residency was generously sponsored in part by Hesty Leibtag and Terry Verk.

That rainbow that is also a bridge (2020); oil on canvas.

Clockwise from left: At Fountainhead Residency, Santibañez references writing from a bathroom wall in a gay bar to inform their work, photographed by Jayme Gershen. Hunter Green Eden (2022), ceramic, leather belt, bandanna, enamel paint. A tattoo artist, part of Santibañez’s practice is etching into leather. Cactus (2020), studs, spikes, wire, epoxy putty, enamel paint, ceramic, and red Georgia clay. A portrait of Santibañez by Gershen.