Time for You: BIPOC Mothers

Angela Davis Johnson, Natalie Ball and Shizu Saldamando

Joining us in June 2022, Angela, Natalie and Shizu are part of Fountainhead Residency's inaugural Time for You: BIPOC Mothers residency, reserved for BIPOC artists who are mothers. This residency is generously sponsored in part by Francie Bishop Good and David Horvitz and the Sustainable Arts Foundation.

Angela Davis Johnson

Angela Davis Johnson is ‘hotfooted,’ a term rooted in Black vernacular to describe the persistent call to move. Like the ancestors of her diaspora - who migrated from place to place, by force and also in search of a better life - Angela sojourns throughout the country, making surrealist work that grapples with what it means to belong. Migration and care fuels her artistic practice. Led by intuition and freedom dreams, she connects geographies, histories, and experiences to her embodied work. She listens deeply and carefully throughout each encounter with land and people, recording those memories and creating paintings, textile, sound, and performance-based works. Her work is both an act of self-care and ancestral regeneration, as she uplifts both the archival and anecdotal histories she researches and gathers throughout her journey; Angela is concerned with liberation, fugitivity, and trauma release practices embedded in Black communities, as a portal through which we can rebuild and reimagine.

Recognizing her work as an opportunity for healing, Angela’s process involves studying family and historical archives as well as Black feminist literature to learn more about the impact of migration patterns, challenges, pitfalls and victories. As she creates the figure, she determines which objects might surround them as a representation of their spirit; these decisions are collaborative and always involve her subject. Completed paintings and tapestries make their way into her performances, which usually find Angela having a spiritual reckoning before them. Angela’s work has been performed and exhibited across the South, including at the Hunter Museum of Art and the Crystal Bridges Museum of Art.

Natalie Ball

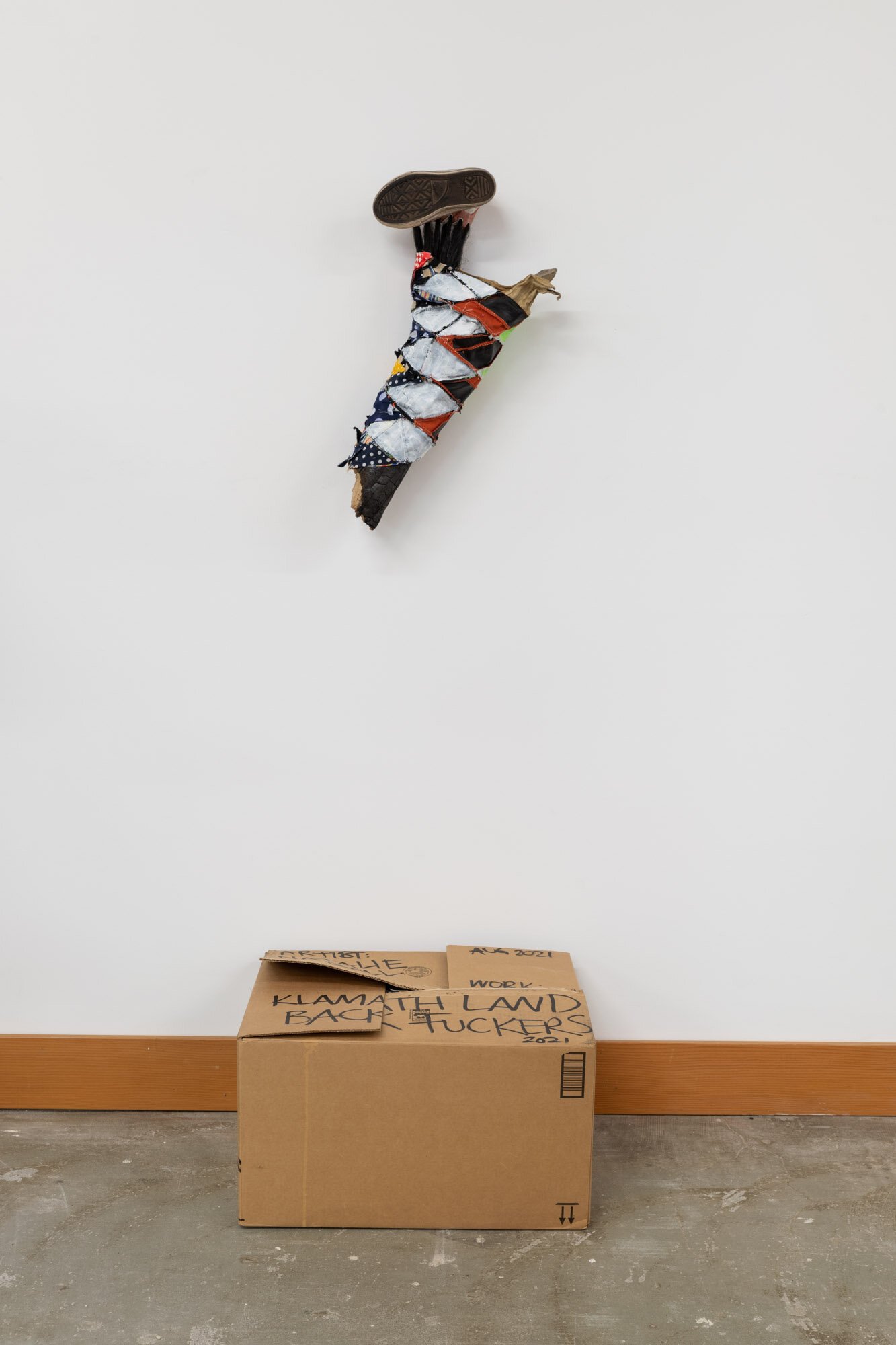

Natalie Ball describes her work as an exercise in self-determination. As an afro-indigenous woman, artist, and mother of the Klamath nation, Natalie’s work considers ideas of belonging, grounded within the sordid history of the United States. From her home in Indian country in Oregon, Natalie uses materials like animal skulls, blankets, quilts, clothing, hair, and grills to create assemblage sculptures. She’s interested in assigning new meanings to the materials she works with by fusing them together and creating a nuanced dialogue. The resulting works are designed to implicate viewers in the colonization of the United States, employing a sense of humor and wit within the work. She views her role as an artist as one of both resistance and community building, holding space for both her tribe members and anyone who wants to get to know their history on a more intimate level, no matter how fraught.

Natalie’s practice is research-based and autobiographical, grounded in both anthropological and and ethnic studies; she will usually draw out stories, parables and archives that point to her ancestors and imagine their re-telling through her material gaze. Natalie’s work can be found in collections like the Rubell Museum and the Hallie Ford Museum of Art. She is the recipient of the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation’s Oregon Native Arts Fellowship (2021), the Ford Family Foundation’s Hallie Ford Foundation Fellow (2020), the Joan Mitchell Painters & Sculptors Grant 2020, Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant (2019).

Shizu Saldamando

Inspired by feminine rituals like communal crafting, Shizu’s painting, video and sculpture practice honors family history and explores the way art can be transformative in illustrating and releasing generational trauma. Fueled by her own history as a Japanese American, whose people were incarcerated in camps following the second World War, Shizu’s work borrows craft traditions like paper flower making to transform traumatic experiences into monuments of collective resilience. Her portraits, once people she met in underground clubs or scenester gatherings, are now based on artists and friends whose work and practice she admires. She specifically chooses subjects who connect with and relate to their own familial and (sub) cultural histories and uses portraiture embedded with craft as a way to honor and recognize them. Shizu engages in communal paper flower making, creating wreaths and floral sculptures on chain-link fence that are born of a collective practice of mourning and meditating on historical systems of incarceration and the violence therein. The flowers are generally made from different materials depending on the context, from organic plant life, traditional Japanese Chiyogami paper or newspaper and historical documents, a radical attempt to transform incendiary media and racist legislation into beautiful, healing wreaths.

Shizu’s process involves documenting friends and fellow creatives with her camera phone. Before she begins painting or drawing in and filling in details of a portrait she projects and outlines the photo onto wood panels, paper, bed sheets, or any other substrate she chooses to work on to keep the proportions right (Shizu suffers from an eye condition known as congenital nystagmus, which makes it difficult to process repeated patterns). Depending on the piece, she then infuses the rendered figure with collaged backgrounds, glitter or other found ephemera. Her flower making work involves talking through and sharing histories, allowing the work to embed these memories in an act of care. Shizu’s work has most recently been exhibited at Charlie James in Los Angeles, at the University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities Gallery, and at the Scottsdale Museum of Art.