July

Making, Melding, and Healing

by Dessane Lopez Cassell

This month’s residency was generously sponsored by Britta Jacobson and Philip Berlinski, and was carried out in partnership with YoungArts.

Nostalgia has gotten a bad rap lately. In our politically polarized era, longing for ‘what once was’ has become a shorthand for regressive desires, a form of rose-colored glasses that would gladly trade an inclusive present for an idealized, exclusionary past. Yet, in the work of Amy Bravo and Priscilla Aleman, who participated in Fountainhead’s July residency, nostalgia operates in good faith, creating spaces in which the possibilities of past and present might be woven together to unspool their mysteries anew.

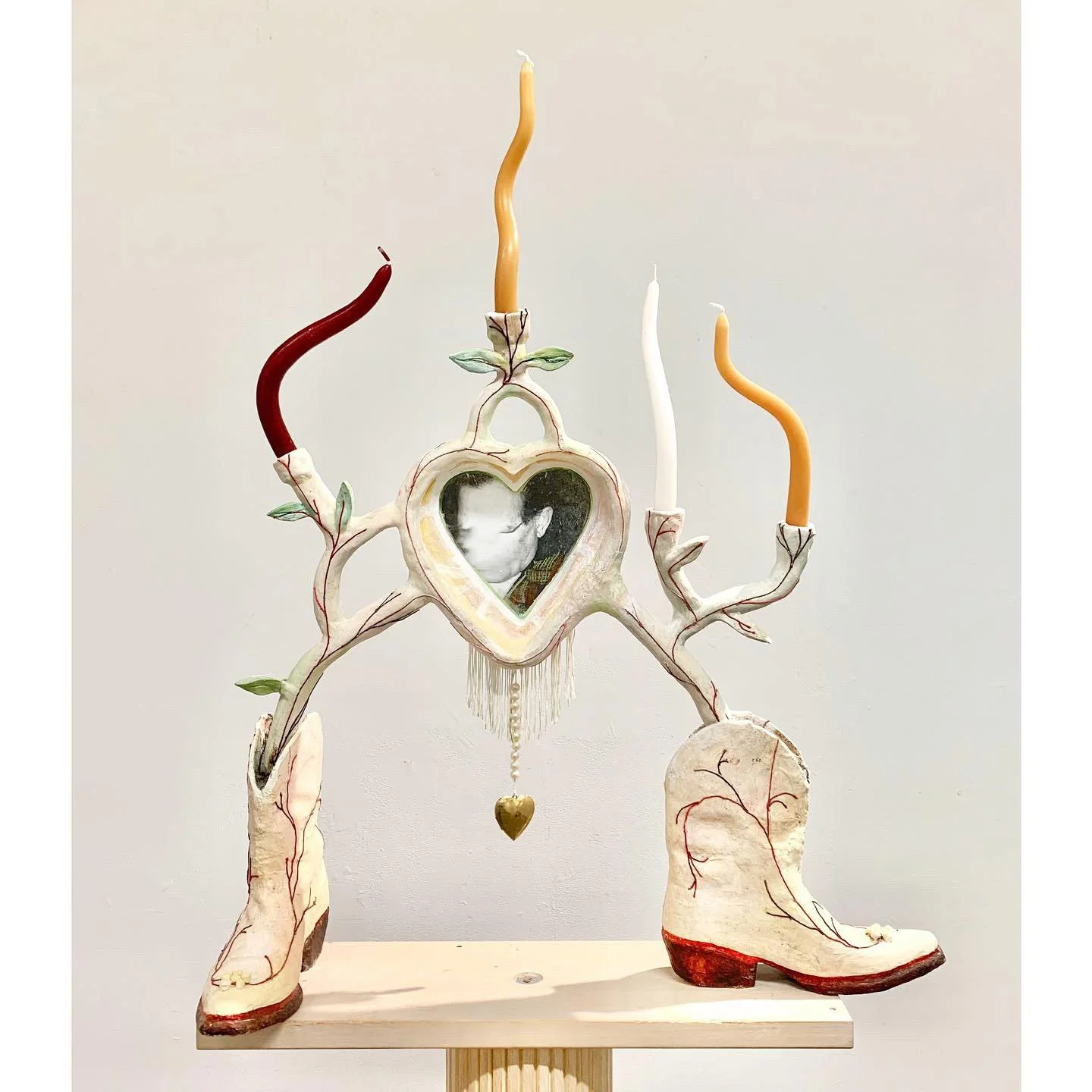

For Bravo, a Cuban and Italian-American painter whose work branches into assemblage, nostalgia offers a vehicle for building her own mythology—one in which home, heritage, and family can sit in right relation to each other, in spite of contemporary schisms and distances. The oral histories of her Cuban grandparents—who immigrated to the U.S. in 1949, ahead of the politically charged exodus of the 1950s—have come to act as the well from which many of her works spring. Stories of their life ranching horses on the island instilled a lingering fascination in Bravo and an affection for an ancestral homeland to which she’s never been. As she explains, “The paintings help me collect their stories, reckon with their beliefs, and investigate questions that can no longer be answered now that they’ve passed.” Chief among those questions is how to reconcile their conservative perspectives and idyllic memories with the island’s more complex political reality.

Yet, beyond trimming the distances of time and geography, Bravo’s odes to Cuba offer something else: fantastical visions of a brazenly fluid and almost eerily sublime landscape—an idyllic Third Space for fellow queer diaspora kids that is “ni de aquí ni de allá.” In her paintings, spectral characters rendered in graphite and wax pastel traverse wide-open landscapes or enact scenes of queer communion, such as in First Gay Bar in Fomento, 2022—its title, a sly nod to her grandparents’ rural hometown. In this sense, Bravo’s work also draws on Foucault’s notion of Heterotopia, through which real sites may be represented only to be inverted or otherwise contested. Speaking with the artist, she chalks this tendency up to a longstanding interest in “botched translation,” here applied to a physical and metaphorical place. Hen Party, 2022, for example, shirks the titular connotations of marriage and heteronormative ritual by rendering two femme-appearing characters on horseback, poised to ride off into the sunset, wearing little more than a t-shirt and cowboy boots. In the distance, a bra-clad character appears ready to chuck a rooster—that omnipresent symbol of machismo—to the wind.

In Bravo’s The Leader of the Calvary, 2022, another massive work on unstretched canvas begun during her time at Fountainhead, a horse appears again, this time charging forth with a gender-fluid (and impossibly flexible) figure on its back. For Bravo, the equine motif is another allusion to her rancher grandfather, perhaps a way of keeping him close. Similarly, the high drama of many of her compositions riff on the camp of Catholic iconography—a trickle-down effect of her Italian-American upbringing and religious abuelos. Here, the animal’s hand-stitched veins and doily heart evoke the immortal steeds of Greek mythology, its raised leg poised to fight off the serpent rearing at its feet.

This melding of diverse spiritual and visual influences is similarly present in the work of Priscilla Aleman, a Cuban and Colombian-American artist whose sculptural practice is informed by her experiences working as an archaeological technician in Miami. The temporary sidestep, from art to social science, renewed her affection for making objects at a time when artmaking had lost much of its allure. Take, for example, Aleman’s long-running series of National Geographic interventions.

The resin-encased collectibles emerged from her broader ruminations on the accumulative impulse that informs archaeological preservation. Over time, she began treating each copy like a sketchbook, writing notes and tearing away layers to expose visual themes across its pages.

“It became this sort of active conversation between me and the text,” she explains. Found objects, such as seashells and plant matter, often make their way into the works, as in I am a Vessel and Oils and Herbs, both 2021. Such materials emphasize Aleman’s understanding of the broader natural world—and not just traditional archaeological sites—as potent realms for “field research,” as well as her nascent interest in Brazilian Candomblé and Afro-Cuban religions such as Santeria.

References to the spiritual abound throughout Aleman’s practice, from her frequent use of the azure hues associated with Yemayá to her emphasis on charm-like sculptural limbs that recall Mexican Milagros. Mi Reina, Mi Cielo, Mi Tesoro (My Queen, My Sky, My Treasure), 2022, one of her main projects during her time at Fountainhead, grew out of an attempt to process a series of spiritual breakthroughs, as well as to recuperate the shattered fragments of a previous work based on a cast of Aleman’s own body. Channeling the visceral emotion of witnessing the violent destruction of a figure so like her own, Aleman reworked its limbs into a gesture of tranquility, clasping one set of its multiple limbs in prayer. The figure’s head is adorned with a crown of Travelers Palm fronds, while her vibrant colored limbs evoke the neon hues of Miami architecture.

Often, there’s a romantic air to Aleman’s work, a fascination with archaeology and historical preservation that hones in on the field’s more noble aspects, while occasionally skirting opportunities to engage more critically with the discipline’s colonial history. Still, as Aleman reflects, her work aims to emphasize healing, rather than “dwell on what’s broken.”

For Aleman and Bravo, reaching back into the past offers a reminder that such vestiges can yield critical insights for the future, particularly when channeled in service of the collective.

Priscilla

Aleman

With a background in archaeology, Priscilla Aleman’s practice retraces ideas around the afterlife, Pre-Columbian cosmology, and the interplay of cultures from the Global South. Her Miami upbringing guides her work of understanding the landscape’s past traditions and its global history. She brings to life her own parallel and intersecting universes spiritually in process and form. Citing the ocean as a connective tissue, Aleman brings together materials collected from related regions throughout the Americas and the Caribbean. She incorporates a multitude of deep field research and works to push the process of recontextualizing old and new worlds. The arrangement of materials in her sculptural installations lends itself to be either collector, creator, analyst, believer, or practitioner. These sculptures, akin to offerings or altars, allow Aleman to chart the waves and ways we are interconnected. Aleman is inspired by powerful spiritual beings, their variations in written and oral histories, and how they shape our understanding of ecological and energetic fields. She equates the practice of thoughtful assemblage with care and ritual, connecting physical and sacred realms.

Aleman has shown new work with the Wavehill Project Space and YoungArts, who previously named her a Presidential Scholar in the Arts. She was recently commissioned for a public work by the New York Botanical Garden. Aleman was born in Miami, FL. She currently lives and works in New York City.

Clockwise from top: In a State of Becoming, 2022. Plaster, paint, collected palm boots, coconuts, mamey seeds, avocados from the Deering Estate, rain water, blue tape, sapote, and ceramic fruits; Guardé estas plumas para que puedas volar (I Saved These Feathers So You Can Fly), 2021. Plaster, mold of grandmother’s hands, blue hurricane tarp, macaw feathers from grandmother’s bird, and newspaper; A portrait of Priscilla Aleman by Cornelius Tulloch; A portrait of Priscilla Aleman in her studio at Fountainhead Residency by Cornelius Tulloch.

Jarvis Boyland

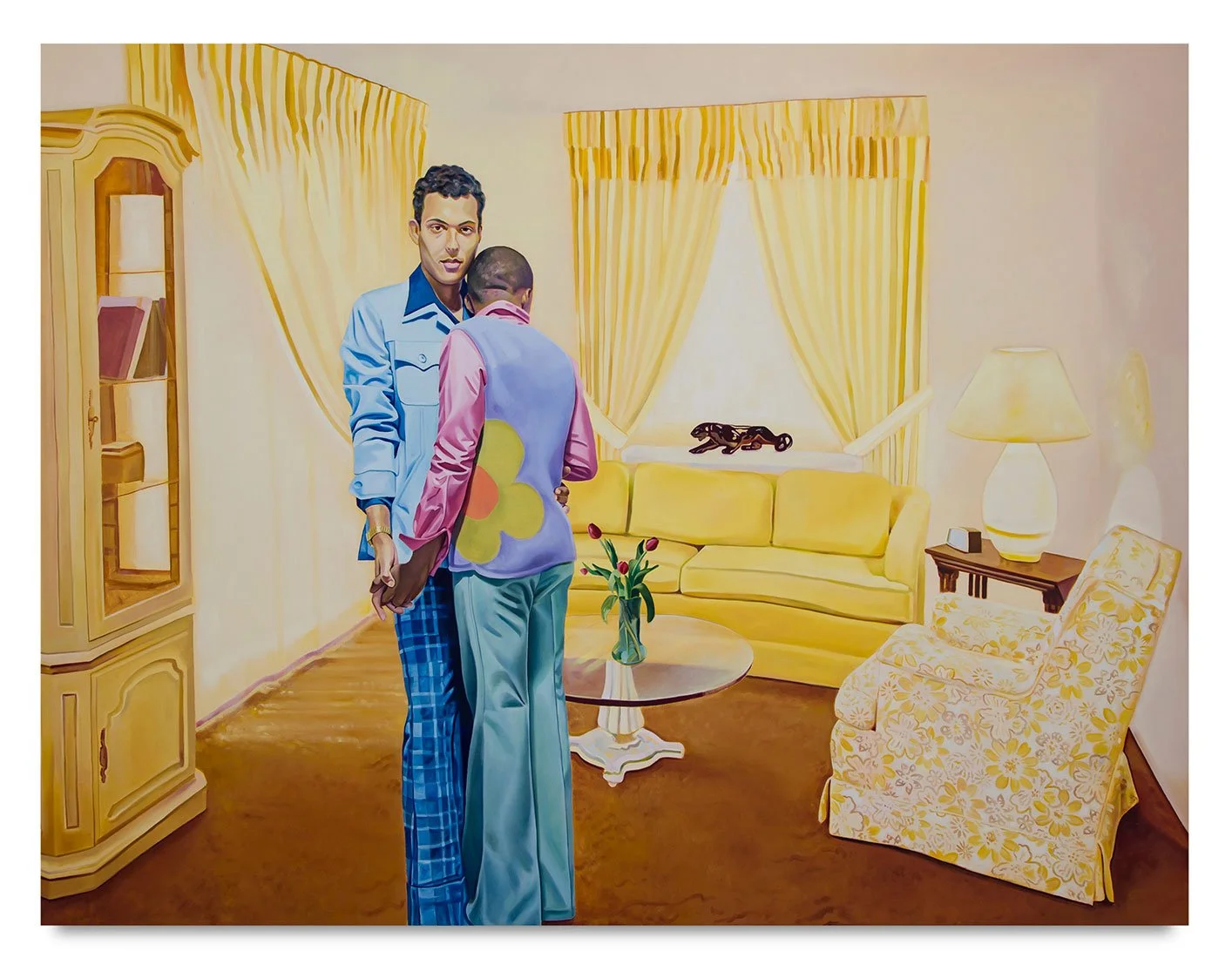

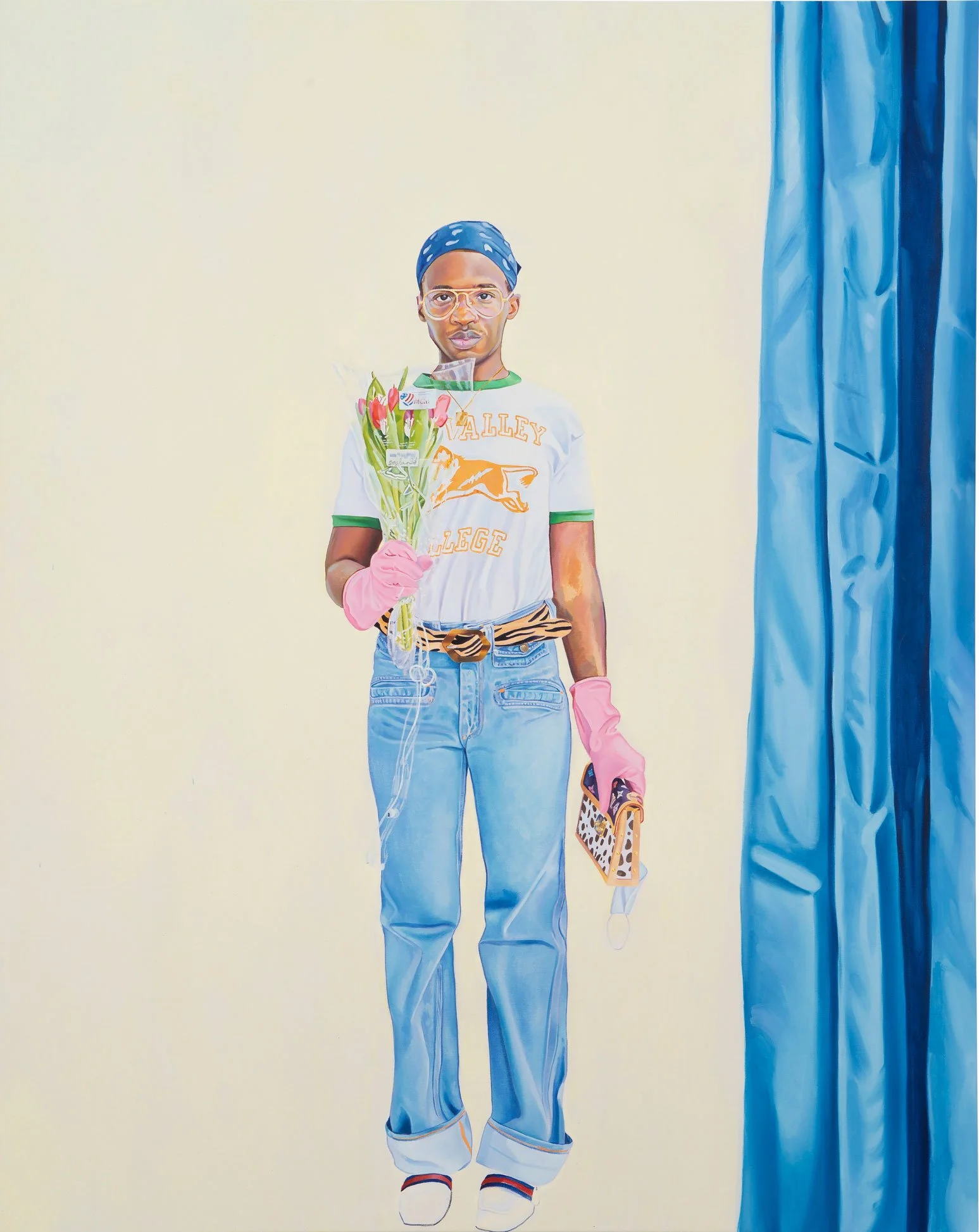

Jarvis Boyland’s work contemplates the past to help us question how we romanticize it. His figurative paintings and drawings conjure retro environments that evoke the 1970s. Through his idyllic color palette and delicate rendering of textiles and flesh, Boyland offers moments of personal reconciliation that traverse time.

Over the years, Boyland has negotiated aspects of his Southern religious upbringing through aspirational images of Black relationships. His sensitively rendered portraits of people from his community, often situated in fictitious domestic environments, consider gender and intimacy. Boyland’s work has been collected by numerous private and public institutions, including the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, and the Brooklyn Museum. Boyland was born in Memphis, TN. He currently lives and works in Los Angeles, CA.

Clockwise from left: A portrait of Jarvis Boyland by Gabrielle Brooks; Bloom, 2020. Oil on canvas; Fool’s Errand 33, 2021. Oil on canvas; Hold Still, 2017. Oil on canvas.

Amy Bravo

Though Amy Bravo has never visited the rural town in Cuba her grandparents left in the 1940s, visions of its lands loom large in her work. Inspired by the memories, histories, and experiences she always heard about and only dreamed of visiting herself, Bravo’s multimedia works are mythical, imaginative journeys across the island. Grounded in this personal narrative, Bravo draws figures into fictional Cuban landscapes in a manner that’s ‘between both here and there,’ as she describes it. Through the work, she attempts to bring her grandparents and their stories back to life, while seating her idealization of their relationship into the reality of family conflict. Themes around queerness, acceptance, and identity are at the heart of her drawings, paintings, and sculptural works. Figures like horses, roosters, and birds intersect with self-portraits rendered in different forms—from bold and courageous, to shy and demure.

Bravo’s process starts with a daydream: she’ll begin drawing on her canvas without any prior sketches. Though she used to draw from photographs, over time she realized she was simply creating ‘different versions’ of herself, and now draws her figures more intuitively. Once her figures are complete, Bravo begins her sculptural assemblage practice, which involves sourcing found objects from her curiosity cabinet. This practice is deeply rooted in her Latinx and familial heritage, which glorifies trinkets and their display. Her completed works are immersive paintings with sculptural elements, bringing the viewer into her inner world. Bravo has recently exhibited at Rachel Uffner (New York), Herrero de Tejada (Spain), and New York University; her work has been featured in New American Paintings, Hyperallergic, and New York Magazine. Bravo was born in Park Ridge, NJ. She currently lives and works in New York.

Clockwise from left: A portrait of Amy Bravo in her studio at Fountainhead Residency by Cornelius Tulloch; Well Done Assassin!, 2021. Acrylic, graphite, flashe, wax pastel, and collage on canvas; A photo of Amy Bravo at work in her studio at Fountainhead Residency by Cornelius Tulloch; The Waiting Room, 2022. Acrylic, wood, graphite, embroidery, plaster, found object, lace, and palm leaf on standing canvas.

Aleman, Mi Reina, Mi Cielo, Mi Tesoro (My Queen, My Sky, My Treasure), 2022. Plaster, milkcrates, gold leaf, basketball, basketball hoops, bird of paradise, pigment, and caution tape.

Aleman, So the Trees Will Fruit, 2020. Collected palm boots, coconuts, mamey seeds, avocados, tree snails, palm tree leaves, mineral pigments, baseball bat, and ceramic fruits.

Aleman, Where the Leaves May Fall, 2021. Vintage National Geographic magazine, croton leaf, and resin.

Boyland, Bloom (detail), 2020. Oil on canvas.

Boyland, Untitled (Recto), 2022. Oil on canvas.

Boyland, Pop Out, 2019. Oil on canvas.

Bravo, Hen Party, 2022. Acrylic, wax pastel, ballpoint pen, and collage on canvas.

Bravo, The Waiting Room, 2022. Acrylic, wood, graphite, embroidery, plaster, found object, lace, and palm leaf on standing canvas.

Bravo, Soul Boot, 2021. Ceramic, plaster, leather cowboy boot, found fabric & object, thread, photo, acrylic, and paraffin candles.