August

Exchanges of Place: What We Learn from One Another

by Folasade Ologundudu

This month’s residency was generously sponsored in part by Adriana and Ricardo Malfitano, and was carried out in partnership with The 55 Project, Fundación El Mirador, and the Haitian Cultural Arts Alliance.

Fountainhead’s thematic residency, Partnering Locally to Reach Globally builds on the ways in which site-specific locations and environments shape our collective memory. In August of 2022, artists Andrey Gûaianã Zignnatto, Vladimir Cybil Charlier, and Ornella Pocetti came together from different parts of what we know as South America and the Caribbean—namely, Brazil, Haiti, and Argentina—to find similarities in their respective practices. As divergent as their ideas and origins are, commonalities can be found in the underlying foundation of each artist’s approach; not only to art making as a discipline, but the larger concepts that are revealed through their layered visual imagery. August’s theme investigates through the lens of each artist’s eye how our sense of place in the world is influenced by forces of power, and the subversion of those powers to explore our identities through avowed narratives of Indigenous wisdom. The artists unearth cultural myths, find hidden truths, and implore viewers to consider how culture deeply impacts our lives and the spaces we inhabit.

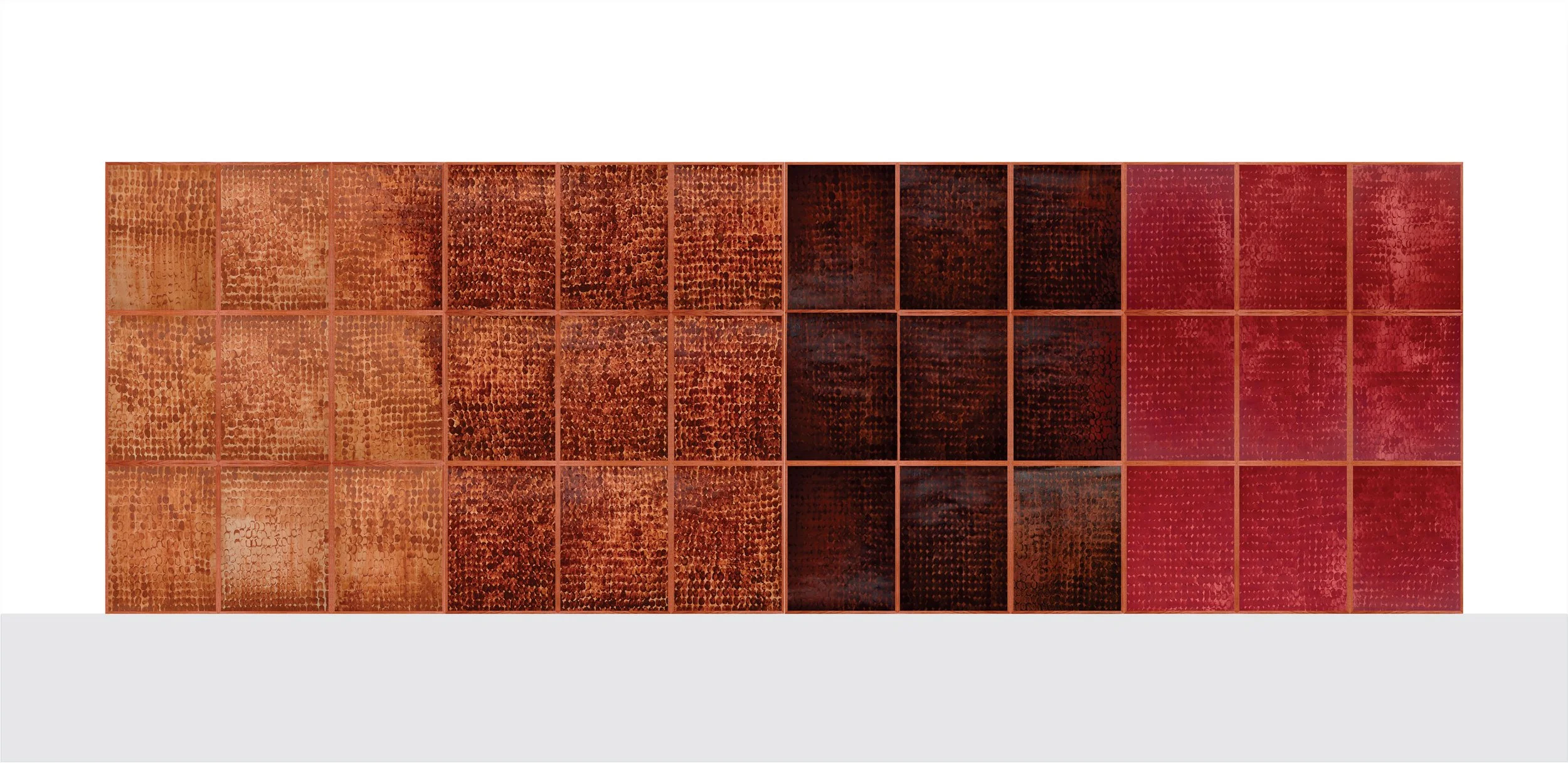

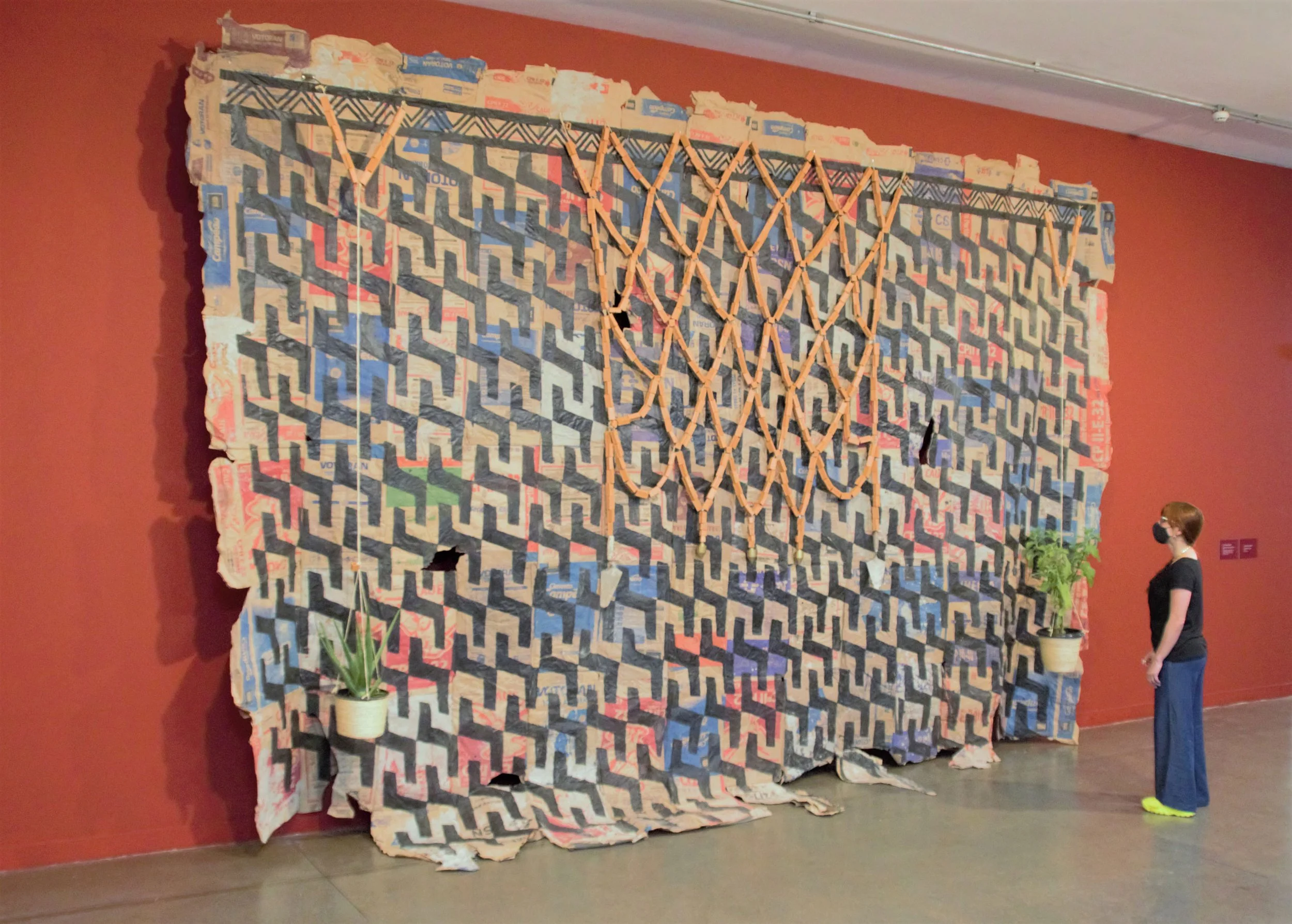

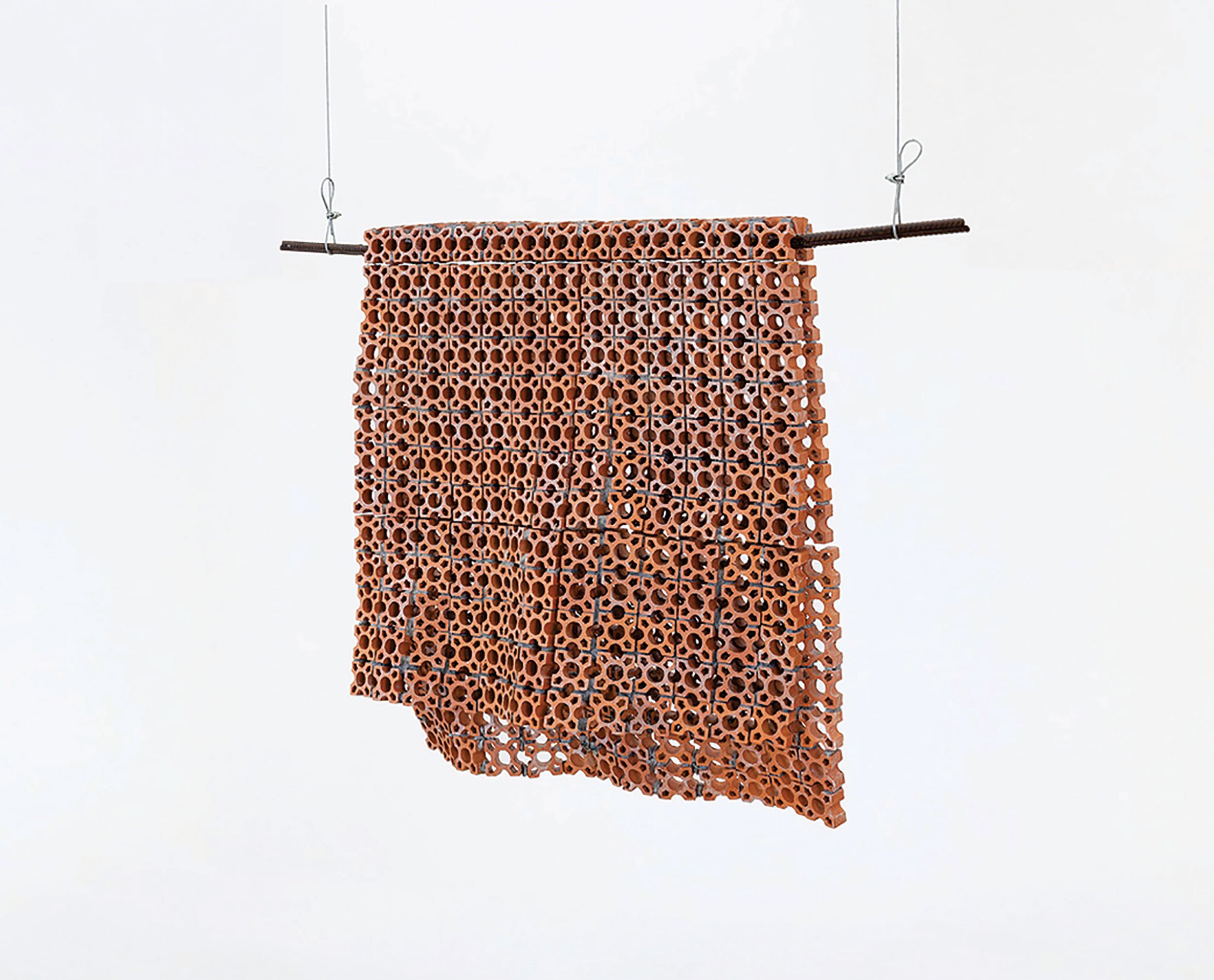

The Indigenous artist Andrey Gûaianã Zignnatto, a descendant from two different Indigenous communities in Brazil, engages in a practice based on ancient rituals and uses brick-laying materials found in construction sites, such as concrete, to create “paintings,” large-scale sculptures, and ceramics. His work spans performance, video, mixed-media collage, installation, and photography. Zignnatto uses his work to wrestle with the disconnection between his ancestral heritage and inhabiting the city of Sao Paulo, where he was born and raised. It is a massive, sprawling, densely populated city of nearly 12.5 million people that has all but obliterated any trace of its Indigenous population. Self-taught, Zignnatto highlights connections between man and nature and asks, “What does it mean to be Indigenous?” He uses his hands and body to make gestural marks and creates patterns through an intuitive process gleaned from aboriginal knowledge. He explores the relationship mankind has to the natural world through paintings and sculptures created with ancient mark-making techniques.

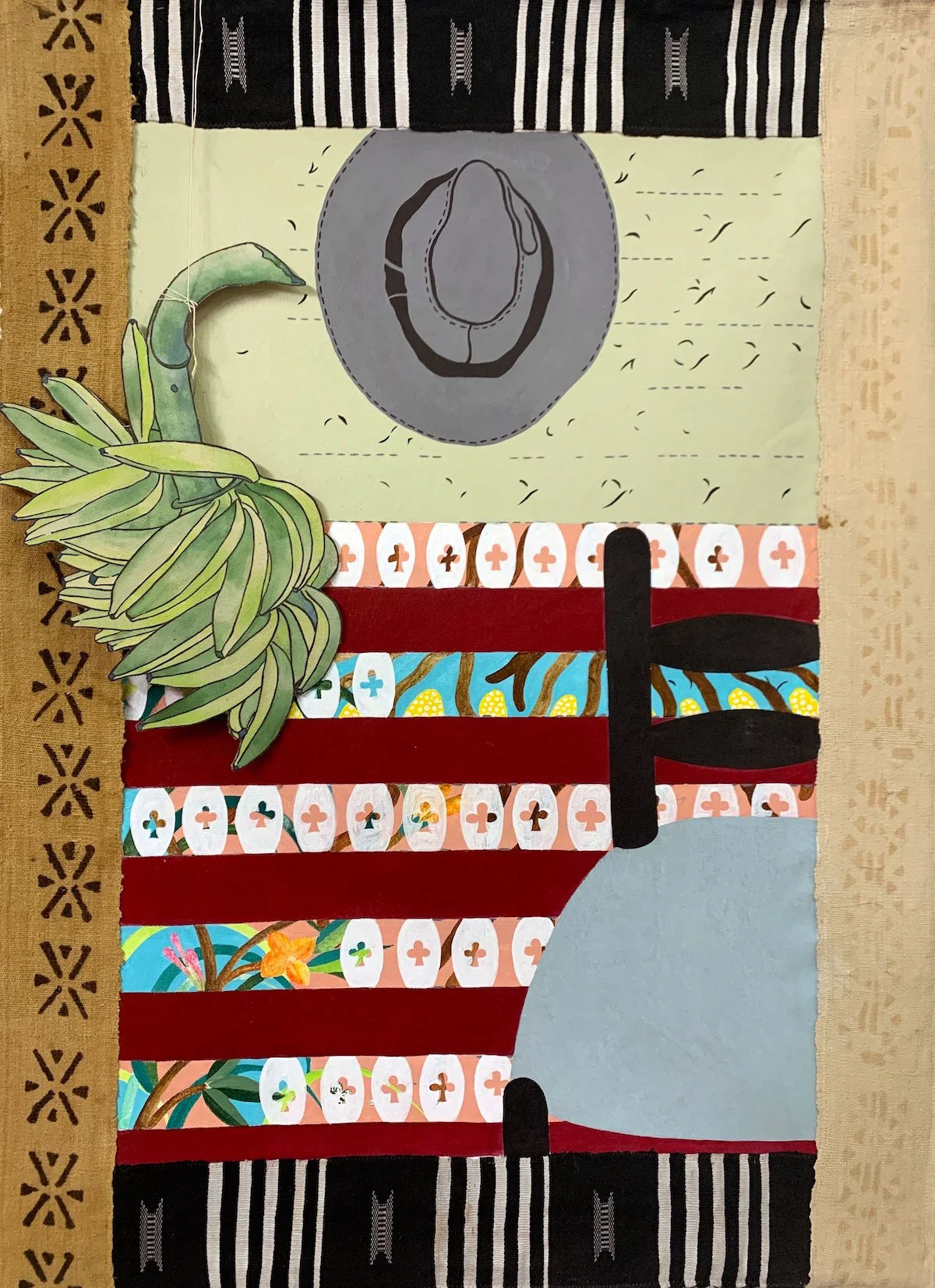

The Haitian-American artist, Vladimir Cybil Charlier, was born in New York City and attended school in Haiti, spending her summers in New York. Today, this experience continues to inform her practice as her layered collage works give way to conversations on identity formation through the diasporic experiences of Afro-Caribbean people. Charlier finds similarities with Zignnatto and Pocetti; most notably in Zignnatto’s tactile use of Indigenous customs and his experiments with materiality; while Pocetti’s fascination with archetypes and mythology is relatable in Charlier’s use of religious imagery within a historical context. Through her detailed motifs combining paint, photography, and African textiles, she takes powerful archetypes seen in religious and traditional Afro-Caribbean folklore such as Haitian Vodou and fashions them anew with present-day Pan-African icons such as Bob Marley, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Frida Kahlo. The artist is informed by an internal dialogue rather than external forces.

Her practice brings together seemingly disparate cultural references from Caribbean and American cultures, generating a new complex narrative for the viewer to decipher.

The Argentinian-born Ornella Pocetti, surveys mythology and the occult through the lens of psychoanalytic discovery popularized in Latin American culture. Her rich and worldly paintings portray female heroines in vivid woodland scenes that straddle imaginary and real landscapes. Elements of grotesque yet equally tender moments reveal Pocetti’s exploration of the contradictions women are faced with in our society. She reflects on violent and problematic ways in which women have been depicted. Pocetti’s art practice includes large-scale painting, ceramic sculptures, and installations. Fictional pastoral vistas create atmospheric works often inspired by horror films and movie soundtracks. For Pocetti, each new work begins with a story; taking shape as either a painting or ceramic, often mixing various symbols from traditional Argentinian folk stories and ancient civilizations. Bold and expressive in her depictions of women, Pocetti studies painting techniques online learning new methods to achieve a style all her own.

Zignnatto challenges the viewer to place importance on the ancient wisdom man has learned from the natural world while recognizing our symbiotic relationship. Charlier uses paintings and mixed-media collages to develop a cohesive language aimed at articulating the nuanced experiences of people who come from diasporic cultures. And finally, Pocetti references the Raphaelite period of art history where reality and wonder collide as she centers her worldly paintings around horror, mystery, and the reclamation of feminism through the body. Each artist focuses on personal experiences and subversions of power structures that have led us to harbor false narratives, to uncover the ways in which we might lead more truthful, honest lives.

Vladimir Cybil Charlier

Over the years, Vladimir Cybil Charlier’s work has focused on developing a cohesive language to articulate a diasporic culture. Mirroring her own trajectory from New York City to the Caribbean, the search for that language has been the thread linking her different bodies of work, whether mixed-media paintings, prints, or installations.

One of her current series, “Pantéon, when the Saints Go Marching!” conflates archetypes of Afro-Caribbean deities with present-day Pan-African icons like Bob Marley, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Frida Kahlo. These mixed-media drapos (hanging textiles) allow Charlier to ignite a conversation about how we form identity and how the Afro-diaspora developed a visual lexicon as a means of adapting to unfamiliar and unforgiving conditions. They also ask the viewer to reflect on how these diasporic practices contrast with our contemporary tendency toward appropriation. Her Old World/New World painting series pieces seemingly disparate cultural references and textures into modernist compositions. These works weave together personal histories with markers from both Caribbean and American cultures, generating a complex narrative for the viewer to decipher. For example, the blue jeans, boots, and straw hats that are recurrent images in the paintings can be read equally as iconic cultural markers that belong to American cowboys or as the sacred attributes of Zaka, the deity of agriculture in Haitian Vodou. The duality and ambiguity leave viewers to ponder how they personally construct meaning.

Charlier has been a resident at the Studio Museum in Harlem. She has been featured in the Venice Biennale and in exhibitions at El Museo del Barrio and the Bronx Museum. She was born in New York City and is currently based in New York.

Clockwise from left: Untitled, Levis, 2022. Acrylic on canvas and linen, muslin, and hand-woven Bogolan strip cloth; Rasin, 2022. Acrylic on canvas, fabric, thread, and handwoven strip cloth; A portrait of Vladimir Cybil Charlier in her studio at Fountainhead Residency by Michelle Lisa Polissaint. Right: A photo of Charlier working in her studio at Fountainhead Residency by Polissaint.

Ornella Pocetti

Ornella Pocetti’s work depicts women as mythological creatures in woodland settings, lending mystery and whimsy to their stories. In her paintings, she references the Raphaelite period of art history to create a style that is both grounded in reality and the wonder of nature. As an Argentinian artist whose culture places an enormous emphasis on psychology and psychoanalysis to truly understand oneself, Pocetti thinks about how feminist theory has been affected or misconstrued by psychoanalysts like Freud or Lacan; working with female figures allows her to reflect on how women have been depicted as hysterical or unreliable, and even ‘monstrous.’ The women in her paintings often appear as grotesque yet equally lovely, signaling Pocetti’s interpretation of the feminine both in psychoanalysis and the history of image-making. Like her depiction of women explores contradictions, their placement within nature has a similar function. Largely detached from nature as a city-dwelling porteña, Pocetti uses nature as a fictional space to make her paintings more enigmatic and atmospheric.

Working with paint and ceramic, Pocetti’s process often involves mining horror films and movie soundtracks for inspiration and studying various painting techniques online to achieve the style she’s trying to create. With minimal sketching, Pocetti takes her time visualizing what she wants the work to look like before she begins painting and tends to add and subtract gestures directly onto the canvas. She has won several distinctions for her work in Argentina, including the Salón Nacional prize in 2021 and the Premio Itaú in 2019. She was born in Buenos Aires, where she currently lives and works.

Clockwise from left: Legendary Sirens, 2021. Oil on canvas; A portrait of Ornella Pocetti by Michelle Lisa Polissaint; A portrait of Ornella Pocetti in her studio at Fountainhead Residency by Michelle Lisa Polissaint; Flutist, 2021. Oil on canvas.

Andrey Gûaianã Zignnatto

Andrey Gûaianã Zignnatto’s work reflects on his ancestral heritage and the realities of living in a city that’s all but destroyed Indigenous ways of life. Based in Sao Paulo, and a descendant of two different Indigenous communities in Brazil, he considers how he can keep those traditions alive by resurrecting both his childhood memories and the ongoing reflections he gleans from spending several days a week working amongst his Indigenous community. His personal crisis—straddling a desire to return to his Indigenous roots while being forced to adapt to modern society—is ever-present in his multimedia works, and he believes that resolving this crisis within the work he makes can serve as a blueprint for healing the divides between the Indigenous and the occidental. Both his materials and processes bring his personal experiences into the work—as a child, Zignnatto supported his family by working with his grandfather as a bricklayer, so he often uses brick, cement, and other construction materials in his work, for example.

Noting that his process is intuitive, Zignnatto fosters a connection with his work by making it simple to understand. He approaches it as an artistic ritual rather than a performance, a painting, or a drawing, so that as many people as possible can understand and access the story he’s trying to tell. Zignnatto’s work has been exhibited in the Museu Afro-Brasil in Sao Paulo, the National Arts Foundation in Sao Paulo, and in the Sharjah Art Museum in the Arab Emirates. He has been awarded the ‘Arte e Patrimômio’ Artistic and Cultural Heritage grant from the Brazilian Institute and numerous commission prizes from the Sao Paulo Culture Department. He was born in Sao Paulo, Brazil, where he currently lives and works.

Clockwise from left: FALESIA, 2022. Earth on paper; A photo of Andrey Gûaianã Zignnatto working in his studio at Fountainhead Residency by Michelle Lisa Polissaint; A photo of Andrey Gûaianã Zignnatto working by Michelle Lisa Polissaint; A portrait of Andrey Gûaianã Zignnatto by Michelle Lisa Polissaint.

Charlier, Payi San Shapo (detail), 2021. Acrylic on canvas and linen, fabric, thread, and handwoven strip cloth.

Charlier, Marassa Andy Basquiat, 2017. Digital print on archival paper.

Charlier, Zaka Blues, 2022. Acrylic on canvas and linen, muslin, paisley fabric, sequins, and beads.

Pocetti, Tesexmataki, 2022. Oil on canvas.

Pocetti, Red waters, 2021. Oil on canvas.

Pocetti, Silverhairs, 2022. Oil on canvas.

Ziggnatto, MESTIZATION - OVER THE SKIN #11, 2021. Jenipapo on paper cement sack, ceramic, brass, vegetable, sisal, and iron.

Ziggnatto, MANTLE, 2015. Iron, ceramic, and epoxy.

Ziggnatto, OVER THE SKIN #01, 2020. Jenipapo, coal, and resin on cement sack paper.