September

Exploring Identity Through the Lens of Technology

by Rob Goyanes

Seung-Min Lee, Allan Pichardo, and Joiri Minaya explore how different technologies impact people and perceptions, from the times of early colonialism to the present age of mass media and machine learning. Their paths and their work are very different from each other, but they converge in interesting, productive ways.

In March 2020 Seung-Min Lee was walking down a Brooklyn street with her boyfriend when two men started chasing her down on their bicycles. They were screaming “China viru!”—“Chinese virus,” the racist, dehumanizing term coined by Donald Trump. Lee, born in Seoul, South Korea, is an artist whose performances are confrontational, and at times uncomfortable for the audience, with satirical roles that pick apart notions of ethnicity. “I’m certainly using identity as a material, but I dont think it’s necessarily what my work is about,” Lee says. “Nor am I trying to fill in the gaps of what you should know about my identity.”

Since 2020, Lee has been addressing the steep rise in anti-Asian violence. In early 2022, Michelle Alyssa Go was pushed to her death on New York’s subway tracks in an act of random racist violence. At the site, Lee tossed Tyvek suits—the protective suits that saturated media images of China during the pandemic—onto the tracks. In photographs of the gesture, the suits look ghostly, balletic. Those that were not totally destroyed, Lee wore as she walked the streets of New York in ritualistic processions.

While in residence at Fountainhead, Lee worked on what she calls “protest paintings.” Made only with gesso, the layer of material that typically goes under oil or acrylic paint, the paintings are all white, like blank protest signs, and some have smudges like those visible on locked device screens. Lee’s experience of the Black Lives Matter protests fomented a desire to return to painting, a quieter, more reflective engagement than her volatile public performances. “I thought maybe I could just be like snow, instead of fire—a blanket to create a sort of climate around the thing, instead of trying to burn things up.”

For his artworks, Allan Pichardo hacks and tinkers with the technology that dominates our media environment, resulting in installations, video games, and subversive user experiences. Creating what he calls “speculative software,” Pichardo clones apps and algorithms in order to examine the underlying, destructive costs of everyday things. “My aim is to see what the machine sees when it’s looking at me,” he says.

During his residency at Fountainhead, Pichardo gathered all the data of his social media presence and created a self-portrait using the tools that are turning society into a strange theater of deep fakes and staged realities. Using his posts and messages, and a program he created based on DALL·E—a software that went viral for the surreal images it produces based on sentences it is fed—the result is an uncanny, bizarre likeness of Pichardo.

Another work, Follow the Drinking Gourd, 2021, is a virtual reality experience inspired by the artist’s Dominican heritage, and the lost histories and data of the Afro-Caribbean diaspora. Users stand on a slave ship looking at the sky, each star representing a modern American song. Clicking on a star, the user is shown the constellation of connections, linking all the way to the African rhythms they are ultimately derived from. Pichardo’s tools are digital, but he shows how technology is used to enforce imbalances in power and oppressive regimes. “I think a lot about our relationship to technology and how we use it in our daily lives,” Pichardo says, “and what that means in terms of our relationship to a corporation like Google or Facebook, and ultimately the government. We have the same exact tools that they do, we just don’t have the scale.”

In 2019, Joiri Minaya cloaked the statues of Christopher Columbus and Ponce de Leon located in downtown Miami in spandex material printed with colorful tropical patterns. “A lot of [tropical patterns] are very decorative and generic, and they use the same plants over and over to refer to places as disparate as the Pacific or the Caribbean,” Minaya says. At first glance, the interdisciplinary artist’s patterns, which she includes in installations, collages, and wallpapers, might not seem too different from these decorative clichés. But they are: these plants have symbolic significance in the religious systems of the African diaspora, plants used in witchcraft and sometimes as poison meant for the colonizers.

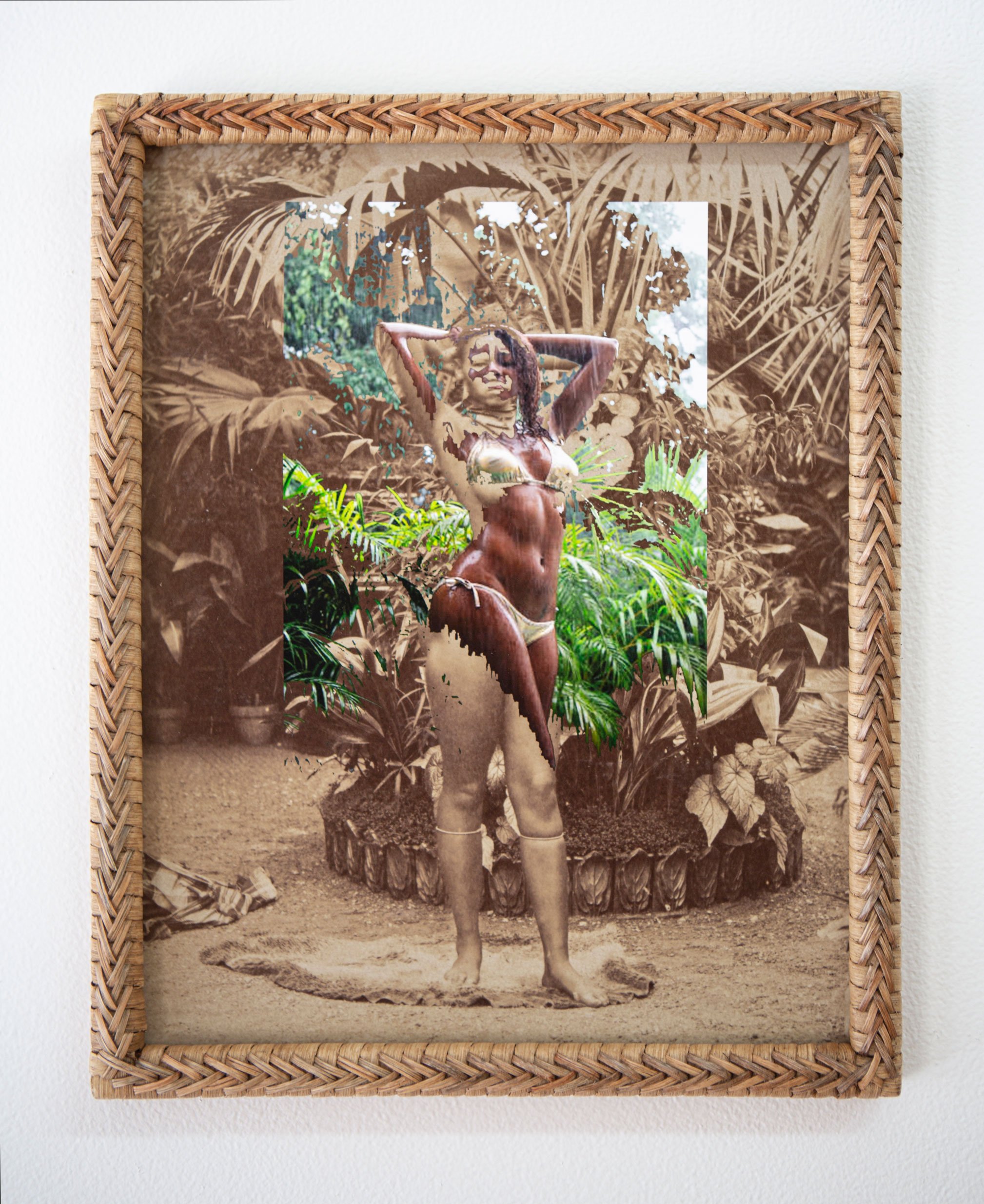

“It seemed that tropical visuals were very prominent in what people imagined my identity to be,” she says. “So instead of fighting those stereotypes, I decided to use that visual language to challenge some of those constructions.” While in residence at Fountainhead, Minaya was finishing work for her 2022 solo show at Praise Shadows Art Gallery, “The Great Camouflage.” The works include images of herself wearing bodysuits she sewed containing illustrations of the castor plant, a species believed to induce invisibility and used as a “war medicine” by the Maji Maji rebellion against German colonial rule.

Countering mainstream liberal notions, Minaya understands that visibility and representation can sometimes be a hindrance to liberation. Minaya’s research-heavy process includes studying the strategies that slaves used to escape. While in the United States that often meant heading north, “in the Dominican Republic,” where she’s from, “that manifested more like running towards the mountain and finding freedom in the wilderness that was impenetrable to the conquistadors.”

Working to understand the structures and everyday processes of marginalization, Minaya, Pichardo, and Lee help audiences understand the nuances of how technology is very often dual-use. Tools that are used to spread bias, hatred, and prejudice can be used to examine and challenge those tendencies, and artists using their own bodies are often at the vanguard of experimenting with them.

Joiri Minaya

Joiri Minaya’s current body of work focuses on the construction of the female subject in relation to nature and landscape in a “tropical” context, shaped by a foreign gaze that demands leisure and pleasure. Like nature, femininity has been imagined and represented throughout history as idealized, tamed, conquered/colonized, and exoticized; she is currently revising existing cultural products that engage in this form of representation and challenging them through her work. Growing up in the Dominican Republic—though born in the United States—how she navigates the global North and South informs her recent work, which expands her initial preoccupations around the body, domesticity, and gender roles into the landscape to unlearn, decolonize, and exorcise larger systems.

Her process is an ongoing exploration across media: a painting or a sculpture might be a departing point for a video or a performance, and they might all merge into a final piece or develop independently. The constant in her work is the presence of the body and the interest in creating distinct power positions with it, often contradictory but operating simultaneously. She studied art at the ENAV (DR), the Chavón School of Design, and Parsons, and has exhibited across the Caribbean, the U.S., and internationally. She recently received a Jerome Hill Fellowship, a NY Artadia award, and the BRIC’s Colene Brown Art Prize. Minaya was born in New York, where she currently lives and works .

Clockwise from left: Continuum (framed), 2020. Archival pigment print; three photos of Joiri Minaya at work in her studio at Fountainhead Residency by Zachary Balber.

Seung-Min Lee

Every project Seung-Min Lee begins starts with thoroughly trying to find the sources of a feeling of alienation she encounters in the daily mundane experience of being in the world. Rage, disappointment, resignation, submission: these are the internal phase changes that alert her to a rift in acclimatization to the “best-fit” diagram of a world that assumes a white body as its subject/customer/end-user. In her performance work, she attempts to inhabit this Other, white, space fully, in an effort to almost empathize with the oppressor, and allow herself to be fully consumed by its seductive power. By allowing her body to be vulnerable and open to this possession in public space, she seeks to create a meaningful tension that can disrupt the supposedly natural order of things. By targeting the materials of everyday life, e.g. the news, food, consumer goods, celebrity, and pop culture, she attempts to defamiliarize the viewer with their assumptions of the distribution of power and meaning, so that they in turn seek to challenge the same.

Lee has performed at Essex Flowers, International Waters, Hauser and Wirth, Luxembourg and Dayan, the Museum of Chinese in America, Artists Space, The Kitchen, Performance Space NY, MoMA PS1, The Shanghai Biennial, Human Resources, LA, NADA, NY, and The Museum of The Chinese in New York. She has been reviewed and published in The New York Times, The New Yorker, Interview, dismagazine, The Guardian, ARTnews, and e-flux’s Art-Agenda. Lee was born in Seoul, South Korea. She currently lives and works in New York.

Clockwise from left: Subway Drawing 1, 2022. Documentation of a performance inspired by recent Asian hate crimes; Protest Painting 3, 2021. Gesso on linen; Untitled, 2022. C-stand, Tyvek suit, and protective masks with artist’s face print; A portrait of Seung-Min Lee in her studio at Fountainhead Residency by Francesca Nabors.

Allan Pichardo is a digital artist that finds the hidden things that modern technology obfuscates about ourselves, and uses code to expose them in their naked form through ‘speculative software,’ or repurposed and hacked applications meant to subvert the original intention of the technology. Presented as interactive installations, net art, video games, and hacked software, his work intends to upend the relationship between consumers of technology and the power structures that exploit them for data.

Pichardo’s work questions what public data says about him as an individual before turning the lens to what it says about society collectively. The answers to these questions guide his approach as he dissects the mechanics of social media to transform mundane interactions into reflective experiences. His background in computer science allows him to engage deeply with the raw materials of computational media—code, electronics, and big data—to extrapolate alternate futures where users have ultimate agency over their personal data. Pichardo’s work has been exhibited in venues in Ohio, Montreal, Chicago, and Portland. He was born in the Dominican Republic, and currently lives and works in Portland, OR.

Allan

Pichardo

From left to right: A photo of Allan Pichardo working in his studio at Fountainhead Residency by Zachary Balber; Talkinghead, 2020. Interactive chatbots; A photo and portrait of Allan Pichardo in his studio at Fountainhead Residency by Zachary Balber.

Lee, Supreme Leader Feed 1 (Kristen the Karen At Work and the iChicken), 2021. Video.

Lee, The Bunker Loop (KIm Jong Un), 2021. Video.

Lee, Intolerable Whiteness, 2018. Video.

Pichardo, Follow the Drinking Gourd, 2021. Virtual reality and custom AI in-game screenshot.

Pichardo, Talkinghead, 2020. Interactive chatbots on crt video.

Pichardo, Stochastic Music, 2022. Interactive networked video. Photo credit Zachary Balber.

Minaya, #dominicanwomengooglesearch, 2016. Photo credit Stefan Hagen.

Minaya, Container #7, 2020. Archival pigment print.

Minaya, Divergences, 2020. Framed archival pigment prints and wallpaper.