July

Alanna

Fields

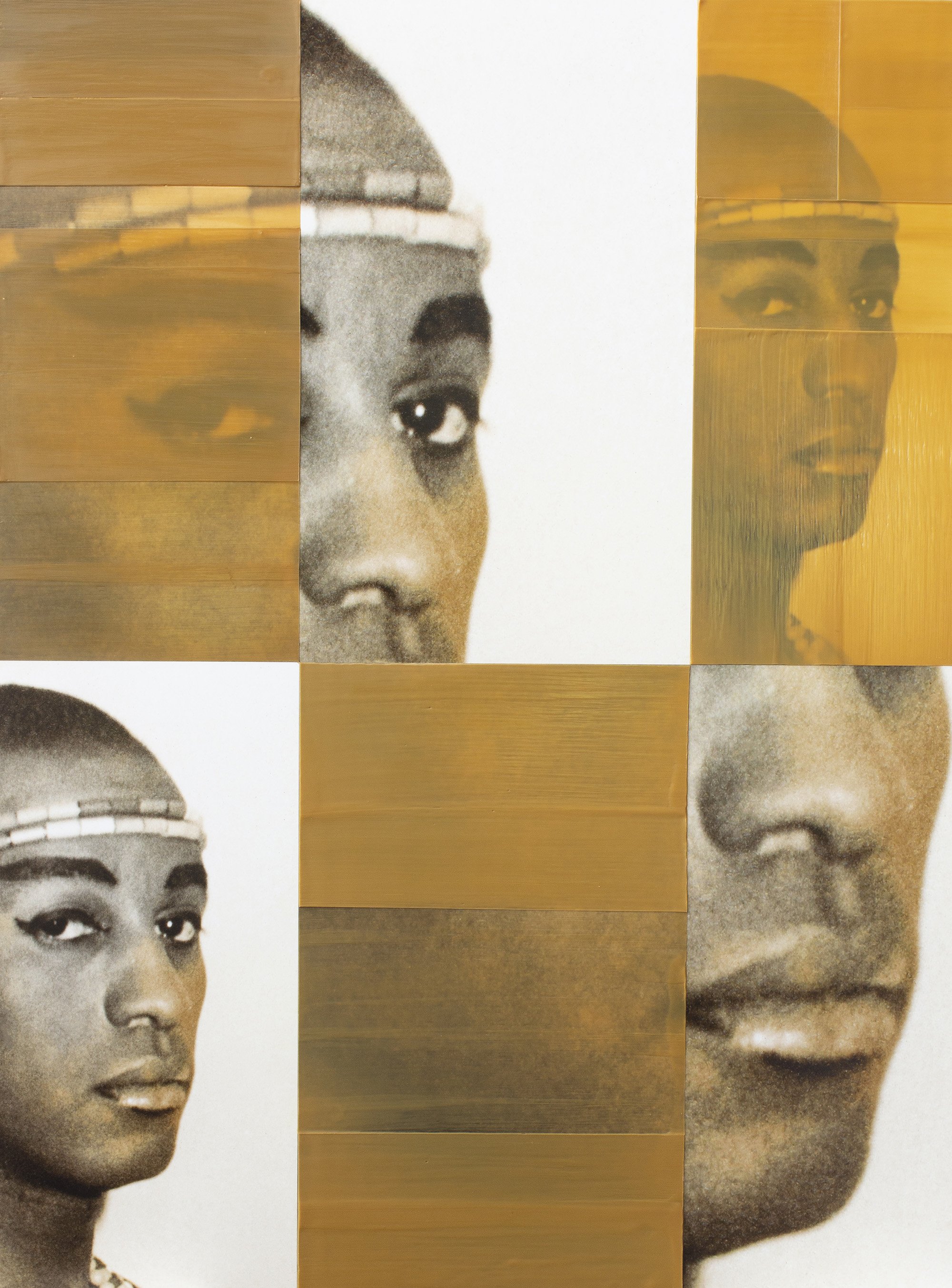

“I’m attracted to the truths that emerge through looking at photographs abstractly,” Fields told me earlier in August, just as she had concluded her residency at Fountainhead in Miami. The intimacy of the images in Fields’s photo-manipulated installations work to enhance and redistribute an archive of Black openly queer subjects across the 20th and 21st centuries to a larger audience. Fields’s images are culled from a personal archive of Black queer relationships. She procures these images from eBay, family photographs, submissions from strangers, or institutional archives like the Faulkner Morgan archive in Kentucky. These photographs, while blown up and sometimes painted over, preserve the temporal and domestic evidence of a photograph as a personal object in her work. Her work acts as material evidence contradicting the pristine historical records of the time that minimize the visibility of Black subjects, let alone Black queer lives.

The artist developed her signature style while in graduate school at Pratt. There, Fields began dipping her printed photographs in wax and was drawn to how the process increased the opacity of the image—becoming a metaphor for how these often-overlooked lives moved through space, seldom seen.

To produce the work, Fields scans her images at the highest resolution and then duplicates the image digitally to crop and enhance features of the photograph that attract her eye. The photographs are mounted onto a durable surface, like aluminum, to then be manipulated further with wax, painting, and ink. These manipulations by Fields demonstrate the artist’s hand and interest in the photograph in that we see the image through Fields’s eyes, and in so doing view it with a tenderness that may not be present with most audiences. At the time of her residency at Fountainhead, Fields’s archive has around 300 objects in it that also include some early daguerreotypes that she plans to work with in forthcoming projects.

–Ayanna Dozier

Alanna Fields’s residency was generously sponsored by Carlo and Micol Schejola Foundation.

Come to My Garden (2021), pigment print, encaustic wax on panel.

Clockwise from left: A portrait of Alanna Fields at Fountainhead, photographed by Jayme Gershen. Fields’s process collages fragments of archival images of queer relationships. Canyons Beyond Time (2021); pigment print, encaustic wax on plexiglass. You Lived Here Inside My Mind (2021); pigment print, encaustic wax on panel. Renard’s Refrain (2021); pigment print, encaustic wax on plexiglass.

Jenelle

Esparza

Jenelle Esparza’s sprawling cotton-weaved sculptures examine how objects and bodies are shaped by environments. The Corpus Christi born- and San Antonio-based artist draws immediately from her natural surroundings to craft work that reflects how cotton fields unearth the exploitative history of plantation labor in Texas. She pays close attention to the racialized lives who made up its labor force, which also include her family history. “Our physical bodies record experiences in one way and the landscape are parallel in recording the experiences in the same way,” she said to me in August.

Esparza records this process through weaving, shifting her focus away from her photographic origins into a process that literally transforms the earth rather than documents it. For Esparza, the material use and transformation of cotton, despite its seemingly abstract outcome, is a way to directly engage with histories that often become abstract through theory. The artist sources her cotton fibers from shops in South Texas that are organic and non-GMO. Esparza then intertwines her weavings with found objects, like wood bark, to repurpose that object while carrying its meaning into the new body of work.

While at Fountainhead, Esparza continued this process in addition to making small studies for larger works that will be on view in a spring 2024 exhibition. This new body of work concentrates on historical narratives tied to the Rio Grande River and the various histories of migration that traverse that pathway. This fascination with the land is intimately connected with the body, as a way to think about it as a retainer of collective memory by which the trauma from colonial records might be repaired. Esparza’s sculptures demonstrate how the South holds memories and insights to navigate the ecological and historical erasures caused by colonialism.

–Ayanna Dozier

Jenelle Esparza’s residency was generously sponsored by Carlo and Micol Schejola Foundation.

Filas II (2018); light box, mirrored plexiglass, 7 copper electroplated cotton spurs, wood, LED lights, Photographed by Charlie Kitchen.

Clockwise from left: Esparza works with a variety of materials, including yarns, cotton spurs, wood and brass. Jenelle Esparza in her studio at Fountainhead, photographed by Jayme Gershen. Through the Threshold (2020), detail showing individual bronze cotton spurs on brass rods, photographed by Jayme Gershen. Esparza experiments with responding study_coconut_miami in her Fountainhead studio. New Growth 01-20 (2021), found objects, cotton yarn, hemp yarn.

Olivia

Jia

Olivia Jia describes her nocturne, blue-cast paintings of books, objects, and the night as psychological self-portraits. Jia’s paintings unearth the depths of her psyche and become a narrative experience through the act of painting. Her work avoids the mimicry of reality to instead submit reality to the interior depths of her mind—excavating memories, experiences, and histories in the process. The nocturnal setting alludes to the heightened activity of the mind at night, or what she described to me as ‘what happens when we are alone with ourselves.’ While dark in aesthetic, the color palette and process emerge as a form of continual self-discovery for Jia, as opposed to a pre-mediated action inspired by a specific genre or mood. In fact, the artist purposefully draws inspiration from multiple genres of paintings across Western and Eastern art histories, including Still Life, Realism, and Huaniaohua (the Chinese tradition of Bird and Flower painting).

Although the artist is rarely directly pictured in the paintings via physical likeness, the work instead captures her through her essence and through the objects that populate the paintings, such as books. In these fictional workspaces, the desks are cluttered with archival documents, family heirlooms, and objects that become a metaphor for the mind. These objects are culled from Jia’s personal archive, which includes cell phone images, museum displays, and memories. The fragmentation of the narrative is critical to Jia’s practice as it becomes a metaphor for cultural heritage and a way to navigate her family history as immigrants from China.

In Jia’s work, the mind is a reflection of the instability of identity and culture, allowing her to question whether these markers are stable, fixed parameters by which the self is configured. Instead, they are always changing and being mixed and molded with parts of past lives and the selves yet to emerge.

–Ayanna Dozier

Olivia Jia’s residency was generously sponsored by Carlo and Micol Schejola Foundation.

Night studio (kingfisher, bone comb, moon through clouds, ink lily) (2023); oil on panel. Photograph by Alina Wang, courtesy of Margot Samel in New York, NY.

Clockwise from left: Olivia Jia in her Fountainhead studio, photographed by Jayme Gershen. Page unfolded (Audubon marsh tern) (2023); oil on panel, photographed by Claire Iltis, courtesy of Fleisher/Ollman in Philadelphia, PA and Workplace in London and Newcastle. Jia’s palette is purposely moody to achieve the appearance of night. Untitled (crane comb and bedroom window) (2022); oil on panel, photographed by Tom Carter, courtesy of Workplace in London and Newcastle. Jia’s brush technique involves fanning the bristles to achieve her desired finish.