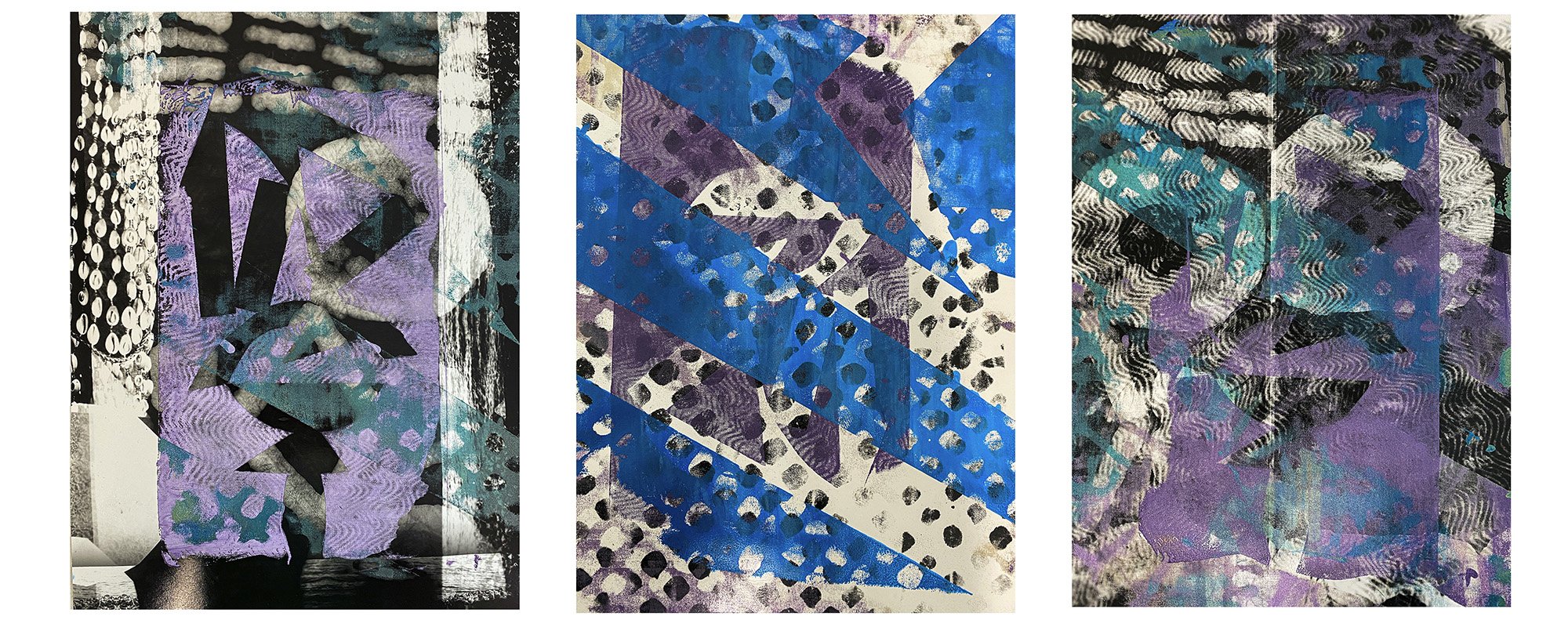

June

Adama Delphine Fawundu

June was a notably rainy month in Miami, and Adama Delphine Fawundu made practical use of the precipitation: Each day, the artist would set out large buckets to collect the rainwater, which she would then mix with cotton pulp. She’d embed this papier-mâché with objects collected both during her Fountainhead residency and throughout her many travels - cowrie shells, feathers, twigs, grains of rice - and these embellished paper pieces were mounted onto the wall, interspersed with indigo cloths and later dyed and painted over. The ensuing work, when i paint myself #1 (2023) was a new direction for Fawundu, who is formally trained as a photographer and tends to work mostly in film, photography and installation. But the perfect confluence of factors allowed Fawundu to expand her breadth significantly in Miami—not just the time and space afforded by a month away from home, but the recent discovery that part of her ancestral roots traced back to Cuba—saw Fawundu experimenting with new materials and references.

“Materiality has become a bigger part of my work,” said Fawundu, “and I’ve begun to source materials from all over the Caribbean, thinking about the conection between all of these locations and references.”

Fawundu’s research-driven process connects to the larger symbolic history of the African diaspora. She’s most concerned with the ashe - the Yoruba philosophy defined as the power to make things happen - and how its developed out of systems that were put in place to annihilate African cultures. She utilizes photography as a metaphor for the ashe, embedding all of her works with negative prints that she screen or block prints before overlaying with found materials.

The buzzing, performative energy found in her work directly references this powerful Yoruba principle, and Fawundu is leaning further into it after her time in Miami. “I’m rethinking how I’m approaching my art by changing my own consciousness and reflecting on how its always changing,” she said.

–Nicole Martinez

Adama Delphine Fawundu’s residency was generously sponsored in part by Sustainable Arts Foundation and Francie Bishop Good and David Horvitz.

when i paint myself #1 (2023); Handmade paper and cotton textile pulp.

Clockwise from left: A detail of when i paint myself #1, which includes cowrie shells, feathers, and Miami rainwater. Fawundu builds when i paint myself #1 in the studio, photographed by Cromwell. Installation view of Wata Bodis at Project for Empty Space; the work is comprised of video collage projections made with scans of fabric, water from the Caribbean Sea and the Wahjai River in Puhejun, Sierra Leone. Untitled, Silver Gelatin with Screen Prints (2022); a triptych derived from Grandma Adama’s fabrics. Fawundu photographed by Rose Marie Cromwell in her Fountainhead studio.

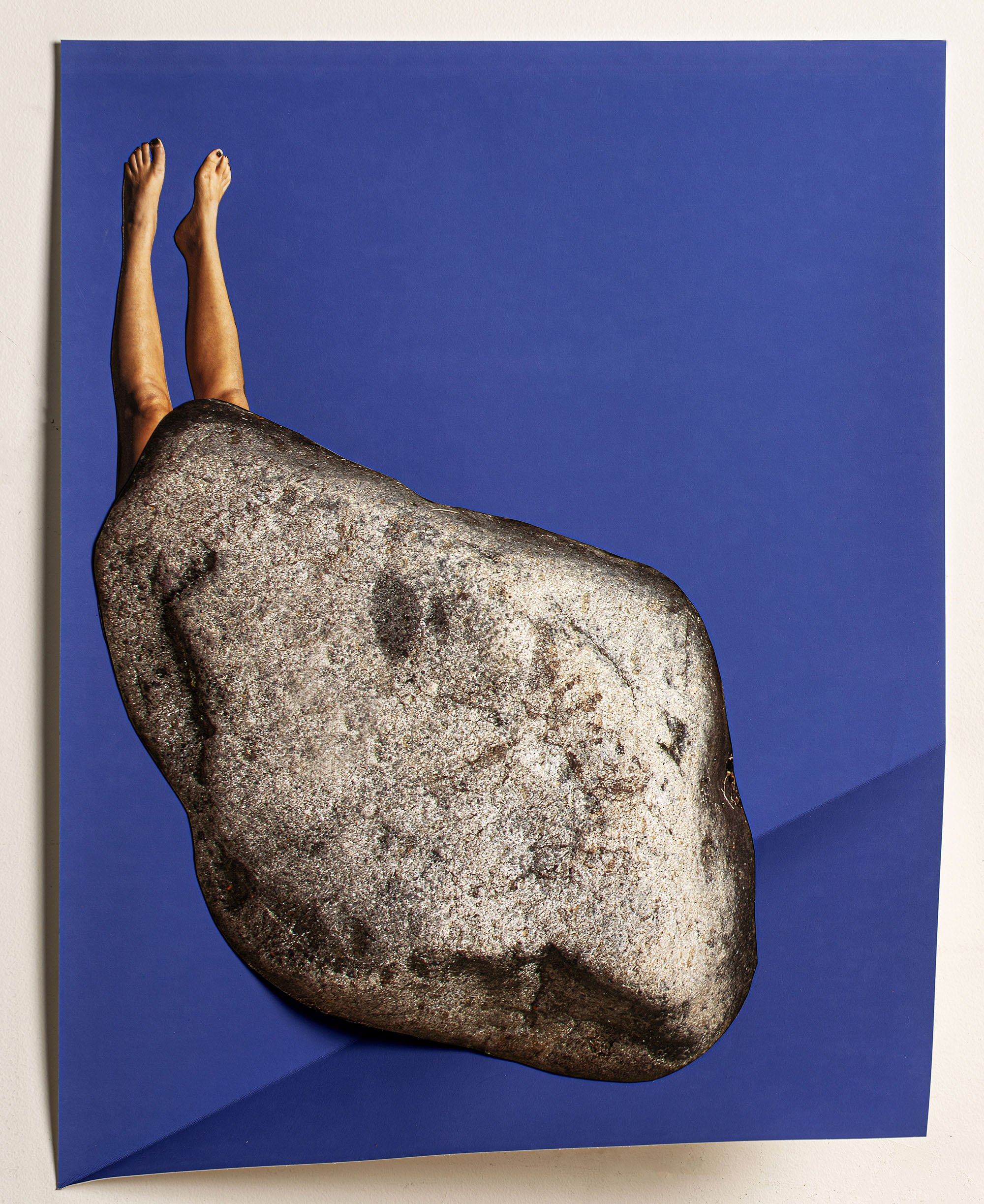

Karina Aguilera Skvirsky

Like many immigrant artists, Karina Aguilera Skvirsky’s work is concerned with belonging. Her practice - which spans performance, photography, film, installation and collage - emerges from an autobiographical journey that meanders into historical terrain. Her deeply researched projects find the artist diving into Inca technologies and philosophies to both make sense of her Ecuadorian heritage and find parallels between Inca life and our modern age. Geometry and architecture are constant references, and photography is always an entry point. More and more, Skvirsky has included self-portraits in her work as a way of revealing her own subjectivity, collaging and cutting up her limbs in a metaphorical process of revealing her many identities to the viewer: Ecuadorian, American, Jewish, mother, artist.

“I started including myself in the work because I realized I had multiple identities and there wasn’t a way to communicate that,” she said. “The work comes out of this weird space of not fitting in, and its recurringly about family history.”

In Miami, Skvirsky built on How to Build a Wall and Other Ruins, a series that was initiated with a Creative Capital grant and interviews engineers, anthropologists, and historians of the Pre-Columbian world about their theories of how Inkans built Ingapirca, an archeological site in Ecuador that uses the same building techniques the Incans used to construct Machu Picchu. Skvirsky collages images of the Incan rock formations with images of her body parts against a richly colored background, a nod to the work of artists like Josef Albers.

Shadow play within these works is a new exploration Skvirsky developed while at Fountainhead. “I kept making maquettes to see if it was going to work out, but I really wanted to see it big,” she said. The resulting works towered on the wall containing all of her parts.

–Nicole Martinez

Karina Aguilera Skvirsky’s residency was generously sponsored in part by Sustainable Arts Foundation and Francie Bishop Good and David Horvitz.

Ingapirca: piedra #19 (verde) (2022); folded and collaged archival inkjet print.

Clockwise from left: Karina Aguilera Skvirsky completes a work in progress at Fountainhead, photographed by Rose Marie Cromwell. Monumento del pasado al futuro #3 (2023); hand cut collage, alpaca, and folded archival inkjet prints, painted frame. Ingapirca: piedra #17 (azul) (2022); folded and collaged archival inkjet print. A portrait of Skvirsky by Cromwell. Monumento del pasado al futuro #1 (2023); hand cut collage, alpaca, and folded archival inkjet prints, painted frame.

Victoria

Udondian

Victoria Udondian tried once before to make it to Miami for a Fountainhead residency, but a global pandemic got in the way. So when she was invited to try again in the summer of 2023, she knew she should jump on the opportunity: Udondian was still reflecting on the closing of How Can I Be Nobody, a large-scale solo exhibition at Smack Mellon in Brooklyn that took over 3,000 hours to make. It wasn’t chance that How Can I Be Nobody swallowed her whole: For the show—a meditation on labor and repressive conditions faced by Black and Brown communities in Africa and Asia—Udondian invited immigrants and first-generation Americans to her studio to work alongside her, where she would collect their migration stories and family histories while casting some of their body parts. The resulting sculptures were installed in boats and beds of flowers, or assembled in towering installations with found textiles as a metaphor of movement and persistent subjugation.

“I wanted to speak to new colonial conditions and how Black and Brown bodies are always questioning and confronting these repressive conditions,” she said. That line of thinking is ever-present for Udondian, who is concerned with revealing how a culture of mass consumption in the West pollutes and enslaves those in the global South. She often uses found textiles - cast off as waste from the U.S. and Europe that winds up in landfills or thrift shops in Africa - to discuss the cycle of harm mass consumption produces.

Between the closing of the exhibition and wrapping up another semester of teaching, the time and space at Fountainhead centered Udondian’s process. She found herself visiting the textile shops that line Little Haiti for European lace, assembling it with other objects in an African hairstyle around a cast of her face. The project derives from research into the white-centric bust sculpture fused with uncovering the architectural influences of African hairstyles of the 1960s.

“Stumbling into this research seated so close to the Caribbean,” she said, “really means something.”

–Nicole Martinez

Victoria Udondian’s residency was generously sponsored in part by Sustainable Arts Foundation and Francie Bishop Good and David Horvitz.

Mme Anam Utom (2023); used coats, epoxamite. Photographed by Etienne Frossard.

Clockwise from left: Ofong Ufok (2019-2022); large hand-woven textiles, second-hand clothes, repurposed textile, rope, dye. Akaisang ye Beyond cages, 1277,1245 (2019-2022); life-cast hands, paverpol, wood, repurposed jewelry, beads, flowers, fabric, and resin, photographed by Argenis Apolinario. Detail of Mma Blue Ided (2023); repurposed textiles, Metal rod, Resin, fabric, rope, wire, wool, mannequin part, found metal, buttons, beads. Udondian stitches together a wide range of materials to make her mixed-media works. A portrait of Victoria Udondian in her Fountainhead studio, photographed by Rose Marie Cromwell.