November

Adelisa

Selimbasic*

Piercings, bikinis, tattoos, cellulite — there’s a lot of tantalizing, sexy detail to absorb in Adelisa Selimbasic*’s paintings. And yet, the work’s depth exceeds its surface elements. The young artist creates figurative pieces that “represent a mood, a vibe” of inclusive, contemporary femininity. In her playful, stylized canvases, she celebrates a diverse range of body types, ethnicities, and personal style. But rather than concerning herself with specific individual’s identities — the way a portraitist might — Selimbašić uses figuration to explore painterly questions of color, light and abstraction, as well as gender expression.

Selimbašić describes her paintings as often “crowded” with figures, sourced from photos of real-life friends, loved ones, and acquaintances. By layering bodies, she pushes beyond scenes of lifelike representation toward more abstract composition strategy. While the painter takes pleasure in illustrating her subjects’ tattoos, jewelry and tan lines, she typically keeps their faces hidden — or rendered with minimal detail. This anonymity has a democratizing effect. In the recent work On Fire (2023), her faceless figures include friends from Rome and people she met randomly at the beach. The bodies are arranged in horizontal bands, as though the figures were collaged together, erasing the illusion of depth. Selimbasic* says she ignored “ordinary perspective,” which implies differing degrees of importance between subjects in the foreground and background. “I like to create a world where there is no hierarchy, and all my muses are at the same level,” she explained.

Her approach to color and light is similarly thoughtful. She uses color for its narrative potential, and aims to include all the hues present in skin — including violets, blues, and greens — in her works. When she uses flat color, by contrast, she does so to represent a light or object outside the picture plane. In I didn’t have the courage to dive (2023) — depicting a group of women swimming — the painter relishes in the play of light and color across water and skin. The pool water’s edge bisects her half-submerged figures, breaking up their curvaceous bodies into strange, seductive abstractions. A belly, a butt, a sliver of arm, float above the surface, tethered to the powerful bodies below. The painting encourages us to look beyond the superficial, to see beauty in human wholeness.

–Wendy Vogel

Adelisa Selimbasic* was the recipient of the 2023 Fountainhead Residency Artist Prize in partnership with Untitled Art, Miami Beach.

Birth Mark (2023); oil on canvas.

Clockwise from left: A portrait of Adelisa Selimbašić in her studio by Zachary Balber. Third Eye (2023); oil on canvas. Selimbasic completes a work in progress in the studio, photographed by Balber. It’s A Pleasure (2023); oil on canvas. Courtesy (2023); oil on canvas.

Ellon

Gibbs

Painter Ellon Gibbs’s recent canvases address humanity’s primal nature. Working in oil and acrylic, he paints what he calls “figures of the spirit” against “fever dreams” of colorful, sometimes fearsome, landscapes. His genderless, faceless figures assume postures such as crouching, grappling, embracing, or standing with a fist raised to the sky. Gibbs says the crouch signifies “birth, death and rebirth” — evoking the protective fetal position as well as prostrate prayer. His paintings equally acknowledge the awesome power of nature in the age of climate catastrophe. In his dynamic works, drama unfolds between human beings and their environment.

Gibbs’s desire to return to primal figuration reflects his relationship to spirituality, as well as his research into non-Western and pre-modern traditions. He describes an embodied connection to the spirit world, expressed through a keen attunement to his physical sensations, gut intuition, and dreams. Born in New York City, his family hails from Grenada and Carriacou in the West Indies. Though he grew up going to Christian church, he says some of his relatives practiced white and black magic, known as Obeah in Grenada. Outside of his familiarity with these rituals, Gibbs studies various texts about religion, the natural world, decolonization and even medieval torture. His sources include botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass and sociologist Mary Douglas’s Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. The artist wishes to understand the origins of our disconnection with nature, and to repair that fractured relationship.

A metaphorical power suffuses Gibbs’s new works. In Here I’m Alive (2023), a figure stands with one arm elevated, surrounded by a wave. Though sublimely beautiful, the arcing spray of ocean threatens to overtake him. In Coming of Age (2023), drying animal skins — like those used for djembe drums — hang above a crackling fire composed of diagonal strokes. A vibrant pink twilight illuminates the scene. At a distance, on the far right, we can see the suggestion of a dark skyline. Gibbs describes a haunting feeling in his paintings, of “very saturated colors [that] jump at you, and then darkness [that] follows it. You almost have to chase the color to feel this sort of connection.” His practice revels in the tension between light and dark, silence and noise, as an analog for humanity’s fraught relationship to nature.

–Wendy Vogel

Lash from the Ocean Created my Struggle (2022); Acrylic paint, oil paint and oil pastel on linen.

Clockwise from left: Here I’m Alive (2023); Oil and acrylic on canvas. I Appeared Normal (2022); oil paint, acrylic paint and oil pastel on canvas. At Fountainhead, Gibbs completed works for an upcoming exhibition at Primary Projects in Miami. A portrait of Gibbs by Zachary Balber. What sweets you destroys you (2023); oil and acrylic on canvas.

Mia

Chaplin

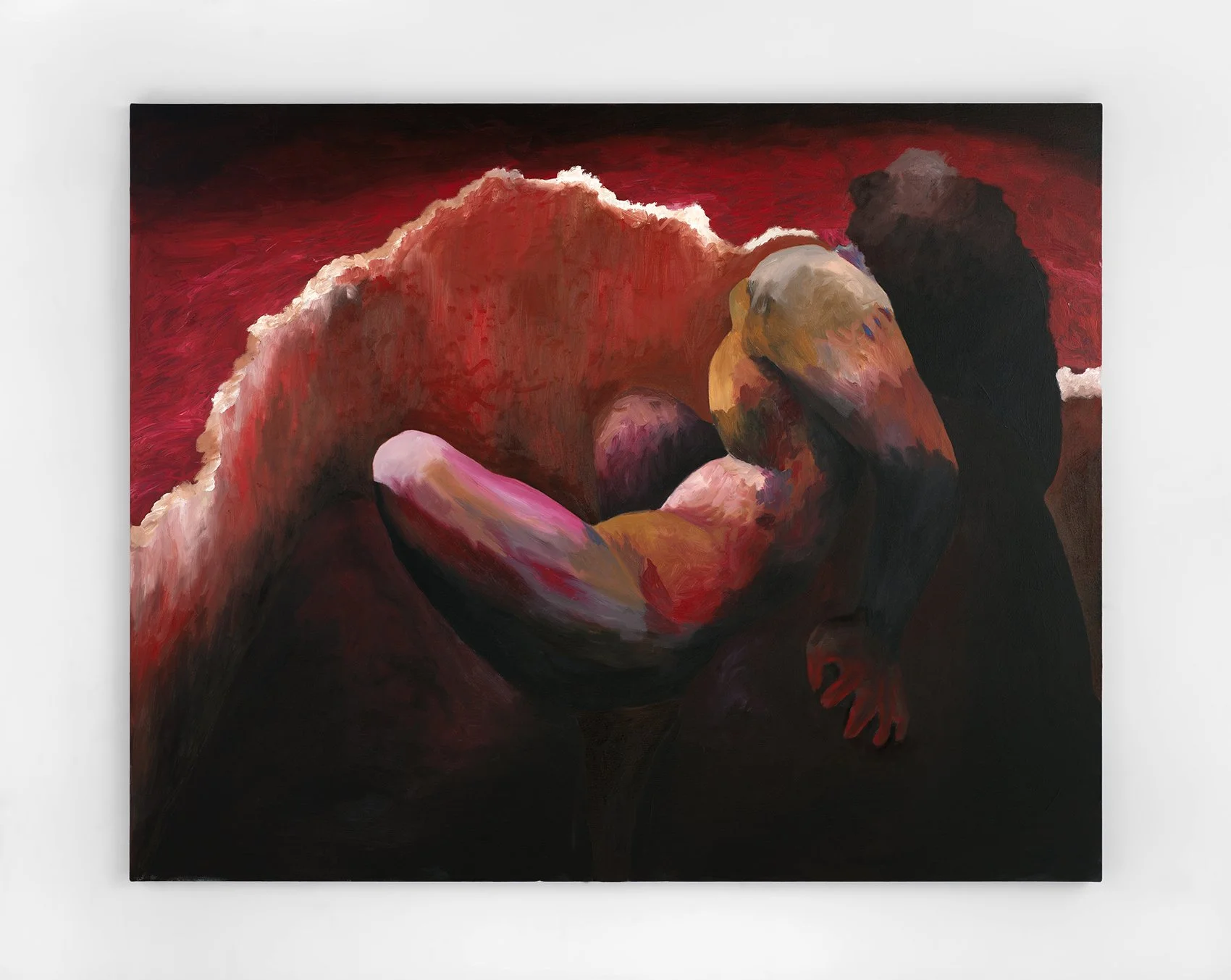

“Women are portrayed in art history as the virgin, the mother or the witch,” said artist Mia Chaplin. “I like to have a woman that encapsulates all those things in one.” Her work expands the vocabulary of feminist representation by combining softness and vulnerability with undercurrents of menace and the grotesque. She is preoccupied by the relationship between sex and violence — specifically, the double-bind faced by women, who must protect themselves and also fight back to reclaim bodily autonomy. In her heavily impastoed paintings and mixed-media sculptures, she teases out dichotomies like living and dying, beauty and ugliness, ferocity and fragility.

Trained as a painter, Chaplin reworks art-historical tropes from a feminist point of view. In this way, her work is reminiscent of artists like Cecily Brown. She begins by creating “glitchy collages” of figures in Photoshop, which she then manipulates by using a digital eraser tool. Her resulting compositions, built up with thick layers of oil, reside between figuration and gestural abstraction.

Theatricality and historical specificity infuse her canvases. She based a recent work, Nymphs (2023), on John William Waterhouse’s pre-Raphaelite painting Hylas and the Nymphs (1896). Waterhouse’s painting made headlines in 2018 when it was temporarily removed from the walls of the Manchester Art Gallery, as part of a feminist intervention by the artist Sonia Boyce. In Waterhouse’s original, bare-breasted, pale-skinned adolescent girls beckon the mythological Hylas into the water; in Chaplin’s Nymph, viewers are plunged into the center of a swampy scene, among densely painted female figures. In terms of stylistic influences, Chaplin points to modernist Frank Auerbach, who uses “basically a swath of color as a leg,” calling his work “beautiful, but also kind of gross.” Soft Shell (2023), Chaplin’s painting of a figure pleasuring themselves, emulates his heavy, wide brushstrokes.

Chaplin began making three-dimensional work around six years ago. She often creates vessels and net-like forms, favoring the materials of wire, papier-mâché and plaster of Paris. While she considers her painted vases reminiscent of a “pregnant belly,” she likens her spiky, wire-gridded vessels — which resemble a cage or a skeleton — as “rebellious,” “anti-mother” forms. Even in these works, the artist undercuts innocence with seediness. On the vase titled Baddie (2023), adorned with flowers, Chaplin has painted self-identified BAD WOMEN pictured with roses, a cigarette, and a knife. Typical of Chaplin’s women, they appear ready to defend themselves at any moment.

–Wendy Vogel

Mia Chaplin was the recipient of the 2023 Fountainhead Residency Artist Prize in partnership with Untitled Art, Miami Beach.

Detail of A Protected Circle (2023); oil on canvas.

Clockwise from left: Installation view of Mia Chaplin’s presentation with What If the World gallery at Untitled Art Miami Beach 2023, for which she was awarded the Fountainhead Residency Artist Prize. Twins (2023); oil paint on canvas. Detail of A Protected Circle (Triptych) (2023), oil on canvas. A third kind of animal (2023); a work in progress at Fountainhead; oil paint, cement, sawdust, adhesives, paper, and wire. Chaplin completes a painting at Fountainhead Residency, photographed by Zachary Balber. Baddie (2023), a work in progress at Fountainhead; oil paint, plaster of Paris, adhesives, paper, and wire. A portrait of Chaplin by Balber.

*Selimbašić