October

Curtis

Santiago

“Whenever I travel, and I start to feel like a foreigner in a foreign land, I find the afro shop to go get a haircut,” says Curtis Santiago. Though the politics, protocols, and audio-visual environments can differ depending on the country he is in—reggae in one, kizomba in another—wherever he is, the Black barbershop provides him with a sense of home. When he was heading to Miami for the Fountainhead Residency for the month of October, Santiago felt some dread about sharing a space with two other artists. “I’m 45,” he said. “I can’t tell you the last time I lived with two people other than my partner or by myself.” But those reservations quickly fell away when Santiago met Gerald Lovell and Xavier Scott Marshall. “It was great to be in the house with two people who immediately became like brothers and homies,” he said.

While in residence alongside the other artists, the Canadian-Trinidadian artist worked on his Infinity series, for the Artissima art fair in Turin, Italy. Started in 2008, the series consists of impossibly small dioramas set in antique and reclaimed jewelry boxes. Each diorama is different. Tableaus of Black figures may be laying in some grass, partying in a living room, or gabbing at the barbershop. One of the dioramas he was working on was a speculative piece. It’s the year 2035, and hundreds of tiny figures from Europe and North America are escaping by boat for South America and Africa, a reversal of the current migrant crisis.

After pursuing a rap career with big ambitions, Santiago decided to switch to visual art full-time. The Infinity series has fulfilled some of the functions he desired from music: access to opportunities around the world, the chance to meet people from many different backgrounds. “For me, visual art is about creating something that provides wonder, or appeal, or escape. Not so much from the academic side—where it’s for those in the know, all theory theory theory,” he said. “It’s still a pop song in a way.”

–Rob Goyanes

Curtis Santiago’s residency was carried out in partnership with Atlantic World Art Fair.

The Gospel According to Lord Blakie (2022); spray paint, oil, charcoal, pastel, and acrylic on canvas

Clockwise from left: Curtis Santiago makes finishing touches on his miniature diorama at Fountainhead Residency. The Party Can’t Done (2019); spray paint, oil, charcoal, pastel, acrylic on canvas. A portrait of Santiago in the studio by Cornelius Tulloch. This drip daemon has demons screaming. On dark days, Saga Bwoys keep it moving through the burning haze (2023); oil stick, oil pastel, spray paint, soft pastel, acrylic paint, acrylic paint marker, charcoal. Like Father Like Son (2023); Mixed media diorama in reclaimed jewelry box.

Gerald

Lovell

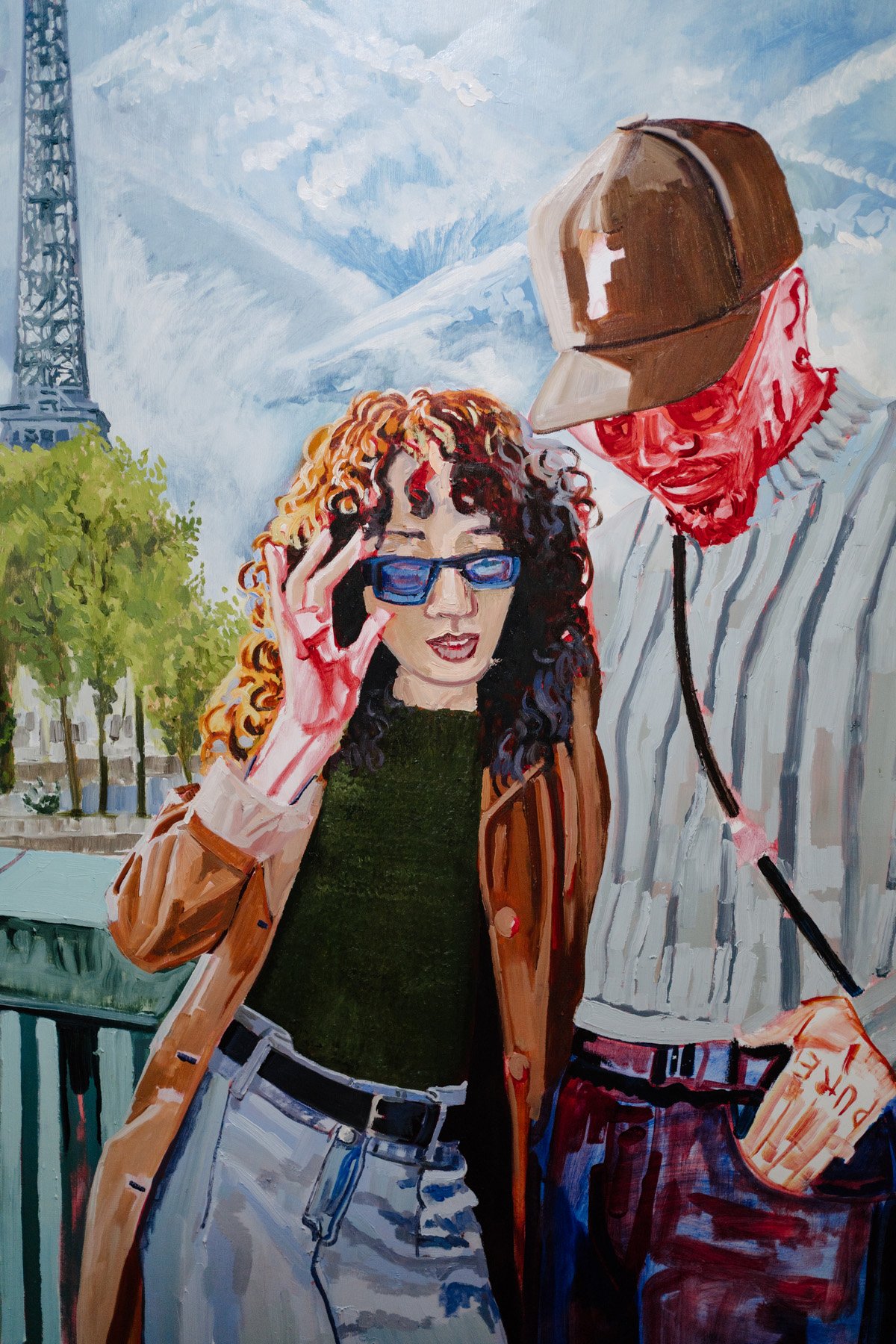

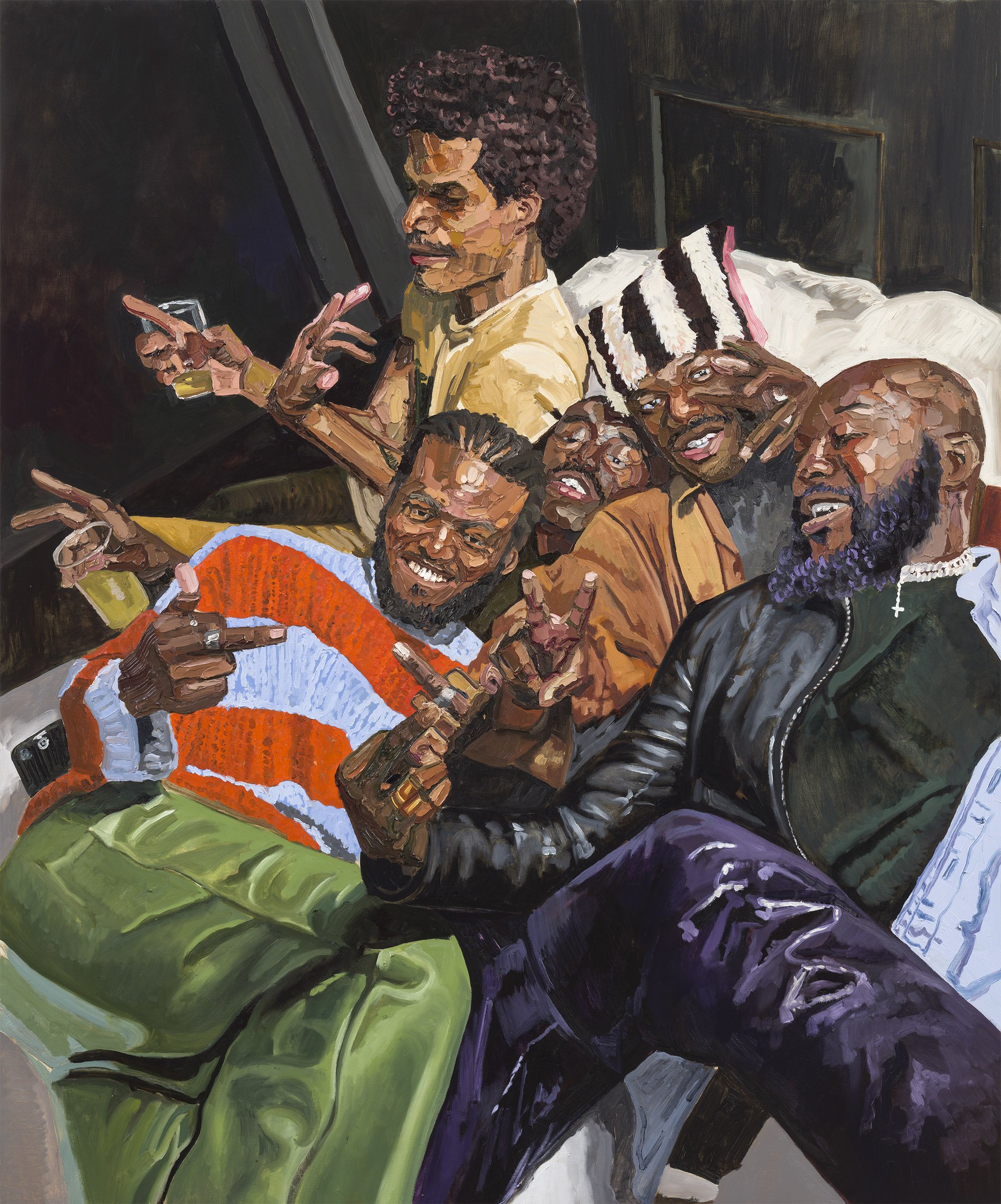

For a work of art to be pop, it often helps if it’s figurative. Gerald Lovell’s Fountainhead residency was spent working on an upcoming solo show with P.P.O.W. “I’ve been doing a lot of Instagram-esque pictures,” Lovell said. “Pictures of my friends on vacation. There’s one painting of my friends in front of the Eiffel Tower.” The paintings, modeled on photos that Lovell takes with his phone, are realistic but with touches of gestural marks, especially on the figures’ skin. By painting Black people without an overt political message, Lovell is probing the limits of Black art today– how it’s made, and perceived.

“There’s a lot of context that goes into the Black figure,” Lovell said. “I one hundred percent get the history of why.” He wants to know when Black artists can simply document their lives, and enter the art canon simply for making great work, rather than communicating a specific politics. “I’m just asking the question: when does the artist or the curator get to have that level of control?” he says. Born in Chicago to Puerto Rican and Black parents, Lovell sees his paintings as a personal photo album, a way to preserve memories and transmit knowledge into the future.

“I always think of the work in the context of years and years after I’m no longer alive,” Lovell said. Cell phones, contemporary clothing styles, people in the midst of hanging out—Lovell’s paintings capture not only a visual record of people now, but also how we understand ourselves as subjects of ubiquitous photography. In other words, candids are increasingly rare: “The phone did a psychological number on us,” Lovell said. “Everyone’s kind of a model now. Everyone poses.”

One of the works for his show at P.P.O.W. is a diptych of him and his friend playing basketball. “I have an annual basketball dream where I play in a league for a day,” Lovell said. He’s played with Lebron James, Derrick Rose, and Kobe Bryant. If it gets sold, the diptych cannot be split into two; they must remain together. “The paintings themselves are starting to have friends.”

–Rob Goyanes

Matt, Sean (a day at Herbert Von King park) (2022); oil on canvas.

Clockwise from left: A portrait of Gerald Lovell by Cornelius Tulloch. Chrissy and Andy in Paris (2023); oil on wood. Chameleon (2021); oil on canvas. Untitled (Christian’s Birthday) (2023); oil on canvas. Lovell works in his studio at Fountainhead Residency.

Xavier Scott

Marshall

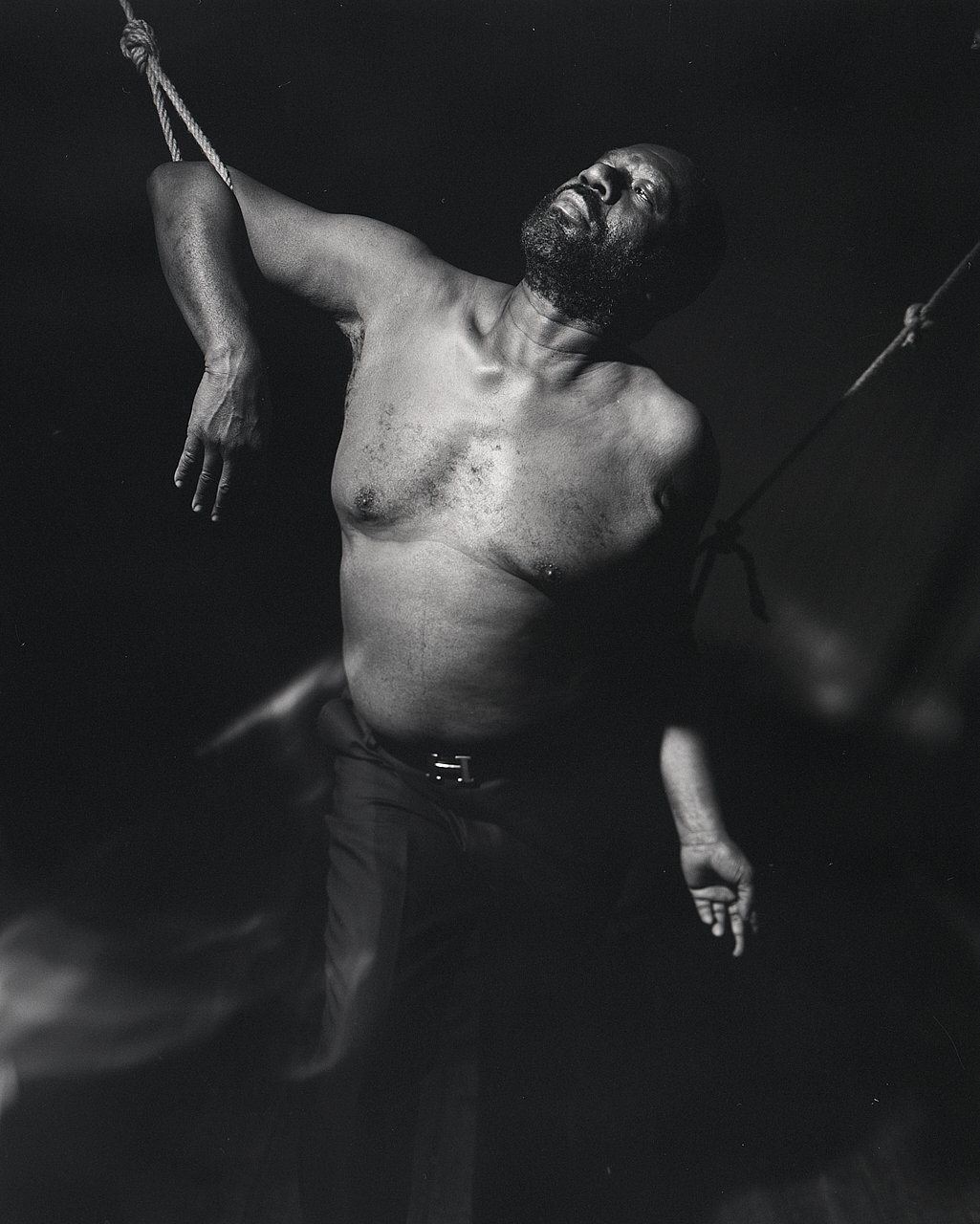

Xavier Scott Marshall is known for his staged recreations of biblical stories and scenes—such as the Caravaggio work The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (1601), depicting Thomas poking Jesus’s crucifixion wound—but with normal, everyday people and objects. Marshall combats the whitewashing of historical figures by photographing people he’s close with, and his goal is to remind people that these stories are closer to our lived reality than the standard visual representations suggest. “St. Sebastian is usually depicted as a very handsome, completely ripped white saint,” Marshall said. “We need to get back to the actual story of what’s going on—it’s the martyrdom, it’s someone being killed for their beliefs.”

Born in New York to a Trinidadian and deeply religious family, Marshall moved to Southern California, where his interest in photography started while him and his friends were skating and hanging out in malls. His family moved to Pittsburgh when he started high school, and Marshall started to understand his photography differently when he visited the area’s museums and saw the work of Gordon Parks, James Van Der Zee, and Robert Rauschenberg. “I was looking at Warhol’s use of repetition,” he said. “The images are acting on you in a way where it’s almost embedding itself into the mind.”

While in residence at Fountainhead, Marshall focused on a single photograph—a woman he saw on the street in New York speaking in tongues, tears streaming down her face. Marshall sat in silence, a witness to her experience, and though he doesn’t usually take candids, he snapped two photographs. He spent the month experimenting with new processes: screen printing the image onto aluminum and cotton paper, applying Warhol’s principle of repetition. He also applied linseed oil to the work, to make it appear as if the image was physically weeping. “It’s like, really huge to be able to expand my practice from photographic works on paper to something with a bit more materiality,” Marshall said.

For each of the three artists, relationships are crucial to their practice. On the process of finding people to photograph, Marshall had this to say: “Regardless of what religion you are, or what your background is, like, that’s not the point behind the images. It’s to communicate, the more you pay attention to people, the more they reveal themselves to you.”

–Rob Goyanes

Madonna And Child (2021); hand-processed.

Clockwise from left: Xavier Scott Marshall hangs works in his studio at Fountainhead Residency, photographed by Cornelius Tulloch. To-Day (2023); inkjet paper transfer on aluminum sheet. The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (2021); hand-processed. A portrait of Marshall in front of A Show of Hands (2021); by Tulloch. Mary Magdalene In Ecstasy (2021); hand-processed.